I have this friend in her early 60s (we'll call her Friend) who recently lamented the financial difficulties of her life. Her granddaughter had recently visited, so of course money was spent and gladly so; and when Friend's birthday came, after a year of scrimping she went and bought herself a little something because dammit, she deserved it. But since she lives the definition of a paycheck-to-paycheck life, these extra expenses simply had to go on a credit card.

Bear in mind: she lives in the fortunate position of being unburdened by credit card debt, which is better than most of us. (In the fourth quarter of 2005, 13.86% of Americans' disposable personal income went toward debt payments. You could almost look at it as a kind of Debt Tax.) So when Friend puts something on a credit card, at least it doesn't join the expenses of all the other times she had to do that. Again, compared to most of the rest of us, that's not bad. (I live for the day when I can pay off my credit cards.)

But. Since Friend's day-to-day finances are stretched so thin, the only way she can pay off this new credit card debt is by doing a balance transfer with a 12-month no-interest-payment deal, then divide her total by 12 and take that amount out of what she would ordinarily put into savings. The effective result: her credit card will be paid off in good time, but she won't be able to save any money for a year. When you're in your 60s, saving money is unbelievably important, but what else can she do?

I have written before about the challenges of what I called being "not-yet-rich." (And thankfully, with the movie coming out, things are starting to look up for me. But that's an avenue that isn't open to most people.) The paycheck-to-paycheck life is terribly difficult--I can tell you from experience that the psychic burden of knowing you can't even go to a movie with friends unless someone else pays just gets bigger and bigger. It's one thing to live with this reality at my age, with my prospects; it's quite another at Friend's age, without those prospects. When your budget is as finely tuned, as carefully crafted, as it can possibly be, but life still keeps throwing you curve balls.

But here's the one wrinkle in all of this: Friend happens to be a deeply religious person, and every month she tithes a significant portion of her income to church-related organizations. It's an extremely worthy thing to do, and I'm not writing in order to denigrate in any way those people who, say, sponsor impoverished children in Africa. After all, compared to their situation, Friend is living the high life. But I do wonder whether there ought to be a little leeway in these churches, so that people whose circumstances are in fact as tight as Friend's could maybe be let off the hook a little.

(I must also, however, note that one of the organizations to which she tithes is the odious Pat Robertson's Christian Broadcasting Network, which is, sad to say, just a revolting waste of good money.)

In that same blog entry from January I wrote about how unsettling it was that I couldn't donate to an environmental organization; but given the state of my finances, it was a sacrifice I had to make and did. At least there wasn't some minister doling out guilt by the bucket for my stinginess of spirit.

It's one thing to be Warren Buffett. His act of unheard-of generosity is, as far as I'm concerned, the single greatest thing anyone has done for the world all year, if not all decade. His gift, combined with the activities of The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, will do enormous good in all sorts of places that need good to be done. But you know what? If Mr. Buffett does indeed give away 85% of his $44 billion fortune, that still leaves him with $6.6 billion. For someone who lives as responsibly, as unostenatiously, as he does, that kind of money will last a nice long time. I think most of us would be very happy indeed with $6.6 billion, no?

But if you're a wage slave like Friend, can't it be enough to just live your life? Not extravagantly but comfortably; particularly in the later years, after a lifetime of devotion and charity. Does Pat Robertson's network really have to keep leaning so hard on people like Friend? People at or nearing retirement age who really need to start taking care of themselves now. Can't it be enough to let the Warren Buffetts of the world take over for a while? Charity is a good and important thing; but what on earth is the point if (a) your charity is in part coerced by your faith, and (b) if it comes at the expense of your own well-being?

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Friday, August 11, 2006

Don't Panic

So it seems that this time the bad men in caves were bad men in apartment flats. What they had in mind was completely awful, and I won't comment on it here because I can't imagine anyone arguing the point that the plot was completely awful.

But the investigation that led to the arrests is interesting and worthy of discussion; so is the response of the air-travel industry to the revelation of the plot. First, the investigation.

I have written before (here and here, among other entries) about what I believe to be gross violations of civil liberties that have been committed in the name of the never-ending War on Terror. But at least from what we know now, none of the tactics that are so offensive--warrant-free wiretaps, torture of prisoners, detention without trial or representation, etc.--had anything to do with the investigation that revealed this latest plot. The Time article mentions that U.S. signals intelligence (the fancy name for wiretapping) was involved in the investigation but doesn't specify whether the communications being intercepted were international or domestic; and in any event, it seems beyond belief that a warrant for wiretapping of these communications would have been denied by a FISA court. (Since the investigation was underway for months, it's also difficult to argue that the "slowness" of the FISA courts would have been an issue--while the last stage of the investigation apparently happened very fast indeed, the initial stages when wiretapping would have been set up seem to have allowed plenty of time to follow the legalities.) There is also no indication whatsoever that detained prisoners from any of our worldwide conflicts provided information relating to this plot; rather, the key tip seems to have come from a member of the British Muslim community, and then good old-fashioned police/intelligence work put one of our people, under deep cover, into their operation.

In other words, the old stand-bys, the legal means of investigation that have worked for years, seem to have come through again. If anything, this latest plot argues that the things we've been lax on--like improving inter-agency communications so that the CIA and FBI aren't working at odds, or improving international cooperation between the western intelligence services--are exactly what produced results this time. And the whole argument about fighting terrorists in Iraq so we don't have to fight them here is severely weakened as we see the continued rise of "homegrown" terrorists like those involved in both the London subway bombing and this latest plot. These were terrorists who don't have to come here because they're already here, they were born here--moreover, their perception of our hatred of Islam, as represented by the conflict in Iraq, was almost certainly part of what inflamed them in the first place.

And now, after revelation of the plot, we are predictably freaking out again. But as this interesting Salon article, written by a commercial pilot named Patrick Smith, points out, this information about liquid explosives isn't new at all. Security experts have known about it for at least twelve years, and it's safe to assume that the reason they didn't make an issue out of it was because they realized how disruptive it would be to travelers. As we saw yesterday. But Smith goes on to make the larger point: "What we need to get through our terror-addled heads is this: It has been, and it will always be, relatively easy to smuggle a potentially deadly weapon onto an aircraft." The man's a pilot; I have to take his word on this.

There is no such thing as perfect security, either in an airplane or on a bus or in a public square. We can only do what we can, as well as we can, but with the knowledge that every once in a while, something is going to slip through. "Acceptable risk" is a bit cold, but it describes the situation we all live in. And it has nothing to do with terrorism, at heart--sometimes planes suffer simple mechanical failures, too, and fall out of the sky. Sometimes a switching mistake happens and one train crashes into another. Sometimes there's something on the road that makes your tire blow out, and next thing you know you're upside down in a creek. Life is risk. Most of the time we know this, but when you add in the looming specter of terrorism, we go all goofy and pretend that if only we sacrifice this, this, this and this, and then this and this as well, we will finally achieve Perfect Safety.

Can't happen. Won't ever happen. And it may seem trivial that you shouldn't ever wear a belt to the airport anymore because it sets off the metal detectors and then you have to get wanded; but we've already accepted a whole series of little compromises, and now we're about to be asked to accept a whole new series of little compromises, and then a couple more years will pass and there'll be some new plot and yet another series of little compromises. Pretty soon we're all putting thousands of miles on our cars because no one wants the hassle of flying anymore, and one of the great conveniences of the last century will be effectively wiped out. All in pursuit of the unattainable goal of Perfect Safety.

But the investigation that led to the arrests is interesting and worthy of discussion; so is the response of the air-travel industry to the revelation of the plot. First, the investigation.

I have written before (here and here, among other entries) about what I believe to be gross violations of civil liberties that have been committed in the name of the never-ending War on Terror. But at least from what we know now, none of the tactics that are so offensive--warrant-free wiretaps, torture of prisoners, detention without trial or representation, etc.--had anything to do with the investigation that revealed this latest plot. The Time article mentions that U.S. signals intelligence (the fancy name for wiretapping) was involved in the investigation but doesn't specify whether the communications being intercepted were international or domestic; and in any event, it seems beyond belief that a warrant for wiretapping of these communications would have been denied by a FISA court. (Since the investigation was underway for months, it's also difficult to argue that the "slowness" of the FISA courts would have been an issue--while the last stage of the investigation apparently happened very fast indeed, the initial stages when wiretapping would have been set up seem to have allowed plenty of time to follow the legalities.) There is also no indication whatsoever that detained prisoners from any of our worldwide conflicts provided information relating to this plot; rather, the key tip seems to have come from a member of the British Muslim community, and then good old-fashioned police/intelligence work put one of our people, under deep cover, into their operation.

In other words, the old stand-bys, the legal means of investigation that have worked for years, seem to have come through again. If anything, this latest plot argues that the things we've been lax on--like improving inter-agency communications so that the CIA and FBI aren't working at odds, or improving international cooperation between the western intelligence services--are exactly what produced results this time. And the whole argument about fighting terrorists in Iraq so we don't have to fight them here is severely weakened as we see the continued rise of "homegrown" terrorists like those involved in both the London subway bombing and this latest plot. These were terrorists who don't have to come here because they're already here, they were born here--moreover, their perception of our hatred of Islam, as represented by the conflict in Iraq, was almost certainly part of what inflamed them in the first place.

And now, after revelation of the plot, we are predictably freaking out again. But as this interesting Salon article, written by a commercial pilot named Patrick Smith, points out, this information about liquid explosives isn't new at all. Security experts have known about it for at least twelve years, and it's safe to assume that the reason they didn't make an issue out of it was because they realized how disruptive it would be to travelers. As we saw yesterday. But Smith goes on to make the larger point: "What we need to get through our terror-addled heads is this: It has been, and it will always be, relatively easy to smuggle a potentially deadly weapon onto an aircraft." The man's a pilot; I have to take his word on this.

There is no such thing as perfect security, either in an airplane or on a bus or in a public square. We can only do what we can, as well as we can, but with the knowledge that every once in a while, something is going to slip through. "Acceptable risk" is a bit cold, but it describes the situation we all live in. And it has nothing to do with terrorism, at heart--sometimes planes suffer simple mechanical failures, too, and fall out of the sky. Sometimes a switching mistake happens and one train crashes into another. Sometimes there's something on the road that makes your tire blow out, and next thing you know you're upside down in a creek. Life is risk. Most of the time we know this, but when you add in the looming specter of terrorism, we go all goofy and pretend that if only we sacrifice this, this, this and this, and then this and this as well, we will finally achieve Perfect Safety.

Can't happen. Won't ever happen. And it may seem trivial that you shouldn't ever wear a belt to the airport anymore because it sets off the metal detectors and then you have to get wanded; but we've already accepted a whole series of little compromises, and now we're about to be asked to accept a whole new series of little compromises, and then a couple more years will pass and there'll be some new plot and yet another series of little compromises. Pretty soon we're all putting thousands of miles on our cars because no one wants the hassle of flying anymore, and one of the great conveniences of the last century will be effectively wiped out. All in pursuit of the unattainable goal of Perfect Safety.

Thursday, August 10, 2006

Screening Dates

Here are the first few confirmed dates when Zen Noir will be opening:

Obviously there's more to come--I don't even know yet which specific theaters the movie will be playing in for most of those cities, and other cities are most definitely in the works. The good people at Magic Lamp are busy busy, and I'll know more soon. (This list on the website should be consistently updated with the newest info on where and when.)

September 15, San Francisco - Lumiere Theater

September 22, Los Angeles - Westside Pavilion

October 13 - Austin, Texas

October 27 - St. Louis and Seattle

November 10 - Minneapolis

Obviously there's more to come--I don't even know yet which specific theaters the movie will be playing in for most of those cities, and other cities are most definitely in the works. The good people at Magic Lamp are busy busy, and I'll know more soon. (This list on the website should be consistently updated with the newest info on where and when.)

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

The Heart That is Hard

I've written often enough about the illegal immigration issue (here, here and here, particularly), so I would have been interested anyway when I saw that Morgan Spurlock's 30 Days program was focusing its second-season opener on the question. But I happen to like the show a lot, so I would've watched anyway. Spurlock is all about life in the real world: he isn't an ideologue, he's someone who asks a question and then tries to find a real, practical answer, usually by going out and living the question and its consequences. In his breakthrough documentary Super Size Me, he subjected his own body to a month of nothing but McDonald's food to see what would happen (it wasn't good); and when he started 30 Days on the fx Channel, he and his girlfriend moved into a crappy apartment for thirty days and lived on nothing but the minimum wage jobs they could get. Again, it was unpleasant for them but revelatory for the audience. Subsequent episodes usually found other participants because Spurlock would probably die if he pulled this stunt too often; but it turned out to be inspired, because putting someone of one viewpoint into the life of someone with another viewpoint may just be the best way, in our media culture, to produce a real Socratic dialogue.

Even so, I found myself deeply moved by this particular episode. The premise was simple: a member of the Minutemen named Frank George moved in with a family of undocumented Mexicans in East L.A. Frank, in an example of particularly good casting, turned out to be a Cuban-born legal immigrant who came to the U.S. with his parents after Fidel happened. (No one ever comments on the fact that his parents apparently had contacts with a U.S. corporation that helped them get documentation--just the sort of wealthy contacts that most Mexican and Central American workers simply don't have. If they did, they wouldn't need to cross the border illegally in the first place. It is the absence of other choices that makes them illegal, as this program would go on to demonstrate convincingly.) What this meant was that, on the one hand, Frank spoke fluent Spanish and was able to communicate easily with the family that took him in; on the other hand, it made him a little self-righteous sometimes about how the path he took to legal status was the one everyone should take. Again: I'm sure most people would, if that option was realistically available to them.

I thought both sides of the issue were well-represented: Frank seemed a true representative of his ideology, although his arguments were a bit limited, usually turning on the idea that this is a nation of laws and, by definition, illegal immigrants are here illegally, therefore they should be deported. The "Gonzalez" family were warm, welcoming, hard-working people making slow steps toward achieving what everyone refers to as the American Dream: opportunity and hard work equals advancement. Their daughter Armida, a 3.8 honors student at her school, was the standout child, widely liked by her teachers and with a wealth of possibilities opening up to her. At the beginning of Frank's time with the family, Armida was hoping to be accepted to Princeton. (How she can be accepted into any college when she's here illegally was never addressed; presumably there's something I don't know about how one's citizenship status interacts with admissions policies.) The Gonzalezes simply insisted that all they wanted was a better life and more opportunities for their children; and the father, Rigoberto, was perfectly up-front about hoping, after a hypothetical amnesty, to one day be able to open his own business, when he would without compunction hire more undocumented workers like himself. (Whether he would then be exploiting his own people is also a question that was never addressed.)

Frank, despite personally liking the Gonzalezes, wasn't about to bend on his principles; then someone came up with the brilliant idea of sending him to Mexico to meet the family the Gonzalezes left behind. This is when the show became really powerful. He saw the hovel the family had once lived in, a roofless pile of cinder blocks without any electricity or plumbing, where water was provided by running a hose from a brackish, almost-certainly infested well dozens of yards away. The conditions were horrifying, and suddenly that 500 square-foot apartment they live in now in East L.A. seemed palatial. Frank met the grandparents who some of the kids have never met, and as a basically decent guy he took some video and showed it to them when he got back to the States.

The question then became: would this experience change Frank's mind? Strictly from watching the show, yes he did, but not entirely: he decided not to go to the border anymore but still supports the stricter version of immigration legislation that was passed by the House. Since the show aired I have seen some reports that Frank felt his "change of heart" was taken out of context, and maybe that's so. But that doesn't diminish the effectiveness of the experience on a random viewer like myself.

Before this gets too long, just a couple points. If, as Frank kept insisting, the problem with illegals is that they're illegal, then what happens if, say, the Senate version of immigration policy is made into law? That would allow a "path to citizenship," and in one of the show's more interesting moments he declared that he was firmly opposed to this version of legislation. But if it did pass, and became law, then would he as a law-abiding citizen support and enforce it? Unfortunately, the participants in this discussion veered away from that question, so I can only guess that Frank would declare it a "bad law" and agitate against it. Trouble is, that in itself pokes a giant hole in his "nation of laws" argument--apparently, we are only to be a nation of laws that Frank likes. And with that, much of the strength of his arguments collapses.

Laws, after all, are not monolithic: we are not meant to serve the law, the law is meant to serve us. If you feel a law is good, great; if you feel a law is bad, then argue against it. Fight against it if you must. (If, for example, a law was ever passed that abridged the freedom of speech, you can bet I would fight against it vigorously.) The question of whether one should simply slavishly follow any law was dealt with pretty effectively at Nuremburg. So, then, Frank does not dislike illegal immigration because it's illegal, he dislikes it because he dislikes it. That's fine, I have no problem with his not liking something; but he needs to be honest with himself and realize that the core of his argument is hollow and he needs a better argument.

Then there's the practical question, which cannot and should not be disassociated from emotional issues. Should we let our raw sentimentality dissuade us from a carefully-considered ethical position? Not usually, no. But after seeing the awful conditions this one family faced when they lived in Mexico, how could anyone with any kind of a soul possibly want to send them back? And given that there are something like eleven million undocumented workers in America, if you sent them all back en masse, where do you think they would live? Probably in conditions that would make that wretched hovel look like a palace.

I absolutely agree that something must be done in Mexico to improve the lives of its citizens. But I say that instead of getting all worked up about the poor workers driven to the desperate point of becoming criminals just to improve their lives a little, I say let's turn our energies to the betterment of Mexico as a whole. That would solve the problem in a way that's good for absolutely everybody, and I just can't imagine why this isn't what everyone is talking about.

POSTSCRIPT: I went on the internet looking for other responses to this powerful program, wanting to read a few reviews from people who had been as moved as I was. Instead, I found this. Oh my heavens. It didn't seem possible that anyone could watch that program and not be moved, and yet here they are, in their numbers. One commenter wrote "[M]y question is why did they not use a red blooded white American person from the Minutemen? Not to be a racist but, Frank did mention he was from Cuba." Yep, that's not racist at all. Oy.

In a web posting, Frank declares that his real change of heart comes in the shape of deciding to start lobbying politicians directly to close down the border, rather than patrolling the border himself. "This change in me was caused by living in a former USA city [East L.A.] that is now a Mexican city to the point that as I wandered the streets I asked the illegals if this city reminded them of a Mexican city and they said yes, Guadalajara Mexico." This, apparently, was a great shock to him.

But parts of Chicago once looked a lot like Krakow. Parts of New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles and other major cities still look a lot like parts of China and/or Korea. And Boston, as I can tell you from personal experience, looks a hell of a lot like Dublin. So what? That's kinda what they mean by "melting pot." The Polish part of Chicago has been mostly assimilated; the assimilation of the Irish and Italians was completed long ago. That's how this works. The fact that part of a U.S. city has changed recently so that it resembles a Mexican city is really not a big deal. I live in L.A., and trust me, it ain't no "former USA city," and the overwhelming majority of it doesn't look like Guadalajara.

Even so, I found myself deeply moved by this particular episode. The premise was simple: a member of the Minutemen named Frank George moved in with a family of undocumented Mexicans in East L.A. Frank, in an example of particularly good casting, turned out to be a Cuban-born legal immigrant who came to the U.S. with his parents after Fidel happened. (No one ever comments on the fact that his parents apparently had contacts with a U.S. corporation that helped them get documentation--just the sort of wealthy contacts that most Mexican and Central American workers simply don't have. If they did, they wouldn't need to cross the border illegally in the first place. It is the absence of other choices that makes them illegal, as this program would go on to demonstrate convincingly.) What this meant was that, on the one hand, Frank spoke fluent Spanish and was able to communicate easily with the family that took him in; on the other hand, it made him a little self-righteous sometimes about how the path he took to legal status was the one everyone should take. Again: I'm sure most people would, if that option was realistically available to them.

I thought both sides of the issue were well-represented: Frank seemed a true representative of his ideology, although his arguments were a bit limited, usually turning on the idea that this is a nation of laws and, by definition, illegal immigrants are here illegally, therefore they should be deported. The "Gonzalez" family were warm, welcoming, hard-working people making slow steps toward achieving what everyone refers to as the American Dream: opportunity and hard work equals advancement. Their daughter Armida, a 3.8 honors student at her school, was the standout child, widely liked by her teachers and with a wealth of possibilities opening up to her. At the beginning of Frank's time with the family, Armida was hoping to be accepted to Princeton. (How she can be accepted into any college when she's here illegally was never addressed; presumably there's something I don't know about how one's citizenship status interacts with admissions policies.) The Gonzalezes simply insisted that all they wanted was a better life and more opportunities for their children; and the father, Rigoberto, was perfectly up-front about hoping, after a hypothetical amnesty, to one day be able to open his own business, when he would without compunction hire more undocumented workers like himself. (Whether he would then be exploiting his own people is also a question that was never addressed.)

Frank, despite personally liking the Gonzalezes, wasn't about to bend on his principles; then someone came up with the brilliant idea of sending him to Mexico to meet the family the Gonzalezes left behind. This is when the show became really powerful. He saw the hovel the family had once lived in, a roofless pile of cinder blocks without any electricity or plumbing, where water was provided by running a hose from a brackish, almost-certainly infested well dozens of yards away. The conditions were horrifying, and suddenly that 500 square-foot apartment they live in now in East L.A. seemed palatial. Frank met the grandparents who some of the kids have never met, and as a basically decent guy he took some video and showed it to them when he got back to the States.

The question then became: would this experience change Frank's mind? Strictly from watching the show, yes he did, but not entirely: he decided not to go to the border anymore but still supports the stricter version of immigration legislation that was passed by the House. Since the show aired I have seen some reports that Frank felt his "change of heart" was taken out of context, and maybe that's so. But that doesn't diminish the effectiveness of the experience on a random viewer like myself.

Before this gets too long, just a couple points. If, as Frank kept insisting, the problem with illegals is that they're illegal, then what happens if, say, the Senate version of immigration policy is made into law? That would allow a "path to citizenship," and in one of the show's more interesting moments he declared that he was firmly opposed to this version of legislation. But if it did pass, and became law, then would he as a law-abiding citizen support and enforce it? Unfortunately, the participants in this discussion veered away from that question, so I can only guess that Frank would declare it a "bad law" and agitate against it. Trouble is, that in itself pokes a giant hole in his "nation of laws" argument--apparently, we are only to be a nation of laws that Frank likes. And with that, much of the strength of his arguments collapses.

Laws, after all, are not monolithic: we are not meant to serve the law, the law is meant to serve us. If you feel a law is good, great; if you feel a law is bad, then argue against it. Fight against it if you must. (If, for example, a law was ever passed that abridged the freedom of speech, you can bet I would fight against it vigorously.) The question of whether one should simply slavishly follow any law was dealt with pretty effectively at Nuremburg. So, then, Frank does not dislike illegal immigration because it's illegal, he dislikes it because he dislikes it. That's fine, I have no problem with his not liking something; but he needs to be honest with himself and realize that the core of his argument is hollow and he needs a better argument.

Then there's the practical question, which cannot and should not be disassociated from emotional issues. Should we let our raw sentimentality dissuade us from a carefully-considered ethical position? Not usually, no. But after seeing the awful conditions this one family faced when they lived in Mexico, how could anyone with any kind of a soul possibly want to send them back? And given that there are something like eleven million undocumented workers in America, if you sent them all back en masse, where do you think they would live? Probably in conditions that would make that wretched hovel look like a palace.

I absolutely agree that something must be done in Mexico to improve the lives of its citizens. But I say that instead of getting all worked up about the poor workers driven to the desperate point of becoming criminals just to improve their lives a little, I say let's turn our energies to the betterment of Mexico as a whole. That would solve the problem in a way that's good for absolutely everybody, and I just can't imagine why this isn't what everyone is talking about.

POSTSCRIPT: I went on the internet looking for other responses to this powerful program, wanting to read a few reviews from people who had been as moved as I was. Instead, I found this. Oh my heavens. It didn't seem possible that anyone could watch that program and not be moved, and yet here they are, in their numbers. One commenter wrote "[M]y question is why did they not use a red blooded white American person from the Minutemen? Not to be a racist but, Frank did mention he was from Cuba." Yep, that's not racist at all. Oy.

In a web posting, Frank declares that his real change of heart comes in the shape of deciding to start lobbying politicians directly to close down the border, rather than patrolling the border himself. "This change in me was caused by living in a former USA city [East L.A.] that is now a Mexican city to the point that as I wandered the streets I asked the illegals if this city reminded them of a Mexican city and they said yes, Guadalajara Mexico." This, apparently, was a great shock to him.

But parts of Chicago once looked a lot like Krakow. Parts of New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles and other major cities still look a lot like parts of China and/or Korea. And Boston, as I can tell you from personal experience, looks a hell of a lot like Dublin. So what? That's kinda what they mean by "melting pot." The Polish part of Chicago has been mostly assimilated; the assimilation of the Irish and Italians was completed long ago. That's how this works. The fact that part of a U.S. city has changed recently so that it resembles a Mexican city is really not a big deal. I live in L.A., and trust me, it ain't no "former USA city," and the overwhelming majority of it doesn't look like Guadalajara.

Tuesday, August 01, 2006

Four Old Guys Singin' Real Nice

When I finally started listening to music around the age of 12 or so, the Beatles came first, as I have written before. When at last my musical tastes began to broaden (ever so slightly), there were three acts that quickly took up second position: The Doors, Simon & Garfunkel, and Crosby Stills & Nash (and Young). On Sunday night, I got to go to a show and see all four members of CSN&Y, in a concert overwhelmingly devoted to protest songs. All the better, I say.

The show was down in Irvine, and we went there because you could get better seats for less money than at the Hollywood Bowl concert Monday night. A bit of a drive, sure, but with nice people and a bunch of CDs, so what? It's a nice venue: yet another of those great Southern California spots where an amphitheatre is built out of a hillside, with trees and grass and very good acoustics. And the weather was fabulous: the awful heat of the last several weeks finally broke a few days ago, and it was so nice to be outside for a while without melting.

What with traffic on the 405, we arrived late--and were just walking to our seats when CSN&Y took the stage, which made for pretty great timing. It took us a little while to get situated and comfortable, and it took the band a little while to get really warmed up, so we were ready for them at about the same time they were ready for us.

The rap against Crosby Stills & Nash, with our without Neil Young, has always been that their live shows can be a bit spotty. It's no great surprise: they are defined by the quality of those gorgeous harmonies, those incredibly well-matched voices, but those harmonies are tough to pull off outside a studio. And indeed, on the second song of the evening, "Carry On," the harmonies weren't working and I was rapidly getting worried. But then they moved into "Wooden Ships," and suddenly it all started to gel.

The problem, we decided, is that Stephen Stills really doesn't have much of a voice anymore. At full volume he can do tough rock numbers pretty well (in fact on one solo turn he sounded almost like Ray Charles), but more delicate numbers seem to be beyond him now. The man is in his early 60s, and it's a shame but these things happen. (He also looks as if the flesh is slowly sliding off his face and onto his neck--who would've thought that David Crosby would be the one looking hale and healthy out of that group?) With one of those four voices struggling, the real close-harmony stuff gets problematic ("Helplessly Hoping," in the second half of the show, didn't come off very well at all); but for songs where Stills could sing out strongly, the four voices mixed very well. And given that there were so many protest songs being played, there actually weren't too many times when delicacy was required of Mr. Stills.

The tour is clearly taking its cue from Neil Young, whose recent album, Living With War, dominates the first half of their show (eight out of ten tracks were played). And since that record, released less than three months ago, is already notorious for its anger toward the current political climate and features a track titled "Let's Impeach the President," small wonder that this CSN&Y tour would lean heavily on tracks like "Ohio," "Almost Cut My Hair," "Immigration Man," "Find the Cost (of Freedom)" and "Rockin' in the Free World." They even played Buffalo Springfield's "For What It's Worth," which was a special treat. (And on which Mr. Stills sounded just fine, thank you.)

The second half of the show made room for more delicate numbers, plus some solo turns or smaller groupings of the four: Crosby and Graham Nash backing up Neil Young for "Only Love Can Break Your Heart," Young and Stills doing another great Buffalo Springfield number, "Treetop Flyer," Nash's "Our House," and maybe the single best performance of the evening, Crosby and Nash doing a delicate, perfect rendering of "Guinivere." (Indeed, Crosby sounded fantastic through the whole night, and a long night it was--35 songs were played, and through all of it, when not playing a guitar Crosby would stand there, his hands in his pockets as if it were all the easiest thing in the world, singing so incredibly well that after his first solo turn I leaned over to Buffie and said "I'm so glad he's not dead!")

Of course, the other candidate for best performance of the evening was "Rockin' in the Free World," which got played about as hard as it could possibly be played, and for a while it seemed the song would never end, that it would just build and build until we all fell over and died, but eventually every single string on Neil Young's guitar got busted and they simply had to stop.

All in all, it was one of the best concerts I've seen. There was a particularly nice segue when everyone left the stage and the legendary recording of Hendrix's Woodstock performance of the Star Spangled Banner was played, which then moved straight into "Let's Impeach the President." Several audience members stood for the Star Spangled Banner, their hands over their hearts as Jimi wailed; then some of the same audience members (it was Orange County, after all) left once "Let's Impeach" got rolling, with its wicked "Flip! Flop!" bridge while video of the President contradicting himself was played on the screens.

Hell of a show. And for my friend Buffie, a musician herself who recently celebrated a birthday, it made for a hell of a nice suprise.

The show was down in Irvine, and we went there because you could get better seats for less money than at the Hollywood Bowl concert Monday night. A bit of a drive, sure, but with nice people and a bunch of CDs, so what? It's a nice venue: yet another of those great Southern California spots where an amphitheatre is built out of a hillside, with trees and grass and very good acoustics. And the weather was fabulous: the awful heat of the last several weeks finally broke a few days ago, and it was so nice to be outside for a while without melting.

What with traffic on the 405, we arrived late--and were just walking to our seats when CSN&Y took the stage, which made for pretty great timing. It took us a little while to get situated and comfortable, and it took the band a little while to get really warmed up, so we were ready for them at about the same time they were ready for us.

The rap against Crosby Stills & Nash, with our without Neil Young, has always been that their live shows can be a bit spotty. It's no great surprise: they are defined by the quality of those gorgeous harmonies, those incredibly well-matched voices, but those harmonies are tough to pull off outside a studio. And indeed, on the second song of the evening, "Carry On," the harmonies weren't working and I was rapidly getting worried. But then they moved into "Wooden Ships," and suddenly it all started to gel.

The problem, we decided, is that Stephen Stills really doesn't have much of a voice anymore. At full volume he can do tough rock numbers pretty well (in fact on one solo turn he sounded almost like Ray Charles), but more delicate numbers seem to be beyond him now. The man is in his early 60s, and it's a shame but these things happen. (He also looks as if the flesh is slowly sliding off his face and onto his neck--who would've thought that David Crosby would be the one looking hale and healthy out of that group?) With one of those four voices struggling, the real close-harmony stuff gets problematic ("Helplessly Hoping," in the second half of the show, didn't come off very well at all); but for songs where Stills could sing out strongly, the four voices mixed very well. And given that there were so many protest songs being played, there actually weren't too many times when delicacy was required of Mr. Stills.

The tour is clearly taking its cue from Neil Young, whose recent album, Living With War, dominates the first half of their show (eight out of ten tracks were played). And since that record, released less than three months ago, is already notorious for its anger toward the current political climate and features a track titled "Let's Impeach the President," small wonder that this CSN&Y tour would lean heavily on tracks like "Ohio," "Almost Cut My Hair," "Immigration Man," "Find the Cost (of Freedom)" and "Rockin' in the Free World." They even played Buffalo Springfield's "For What It's Worth," which was a special treat. (And on which Mr. Stills sounded just fine, thank you.)

The second half of the show made room for more delicate numbers, plus some solo turns or smaller groupings of the four: Crosby and Graham Nash backing up Neil Young for "Only Love Can Break Your Heart," Young and Stills doing another great Buffalo Springfield number, "Treetop Flyer," Nash's "Our House," and maybe the single best performance of the evening, Crosby and Nash doing a delicate, perfect rendering of "Guinivere." (Indeed, Crosby sounded fantastic through the whole night, and a long night it was--35 songs were played, and through all of it, when not playing a guitar Crosby would stand there, his hands in his pockets as if it were all the easiest thing in the world, singing so incredibly well that after his first solo turn I leaned over to Buffie and said "I'm so glad he's not dead!")

Of course, the other candidate for best performance of the evening was "Rockin' in the Free World," which got played about as hard as it could possibly be played, and for a while it seemed the song would never end, that it would just build and build until we all fell over and died, but eventually every single string on Neil Young's guitar got busted and they simply had to stop.

All in all, it was one of the best concerts I've seen. There was a particularly nice segue when everyone left the stage and the legendary recording of Hendrix's Woodstock performance of the Star Spangled Banner was played, which then moved straight into "Let's Impeach the President." Several audience members stood for the Star Spangled Banner, their hands over their hearts as Jimi wailed; then some of the same audience members (it was Orange County, after all) left once "Let's Impeach" got rolling, with its wicked "Flip! Flop!" bridge while video of the President contradicting himself was played on the screens.

Hell of a show. And for my friend Buffie, a musician herself who recently celebrated a birthday, it made for a hell of a nice suprise.

Friday, July 28, 2006

Not My iPod

Okay, I love the iPod as much as anybody, but come on...

Do products have "jump the shark" moments like TV shows? 'Cause it's hard to imagine a better one for the iPod. (And yes, as far as I can tell, this is completely legit.)

Do products have "jump the shark" moments like TV shows? 'Cause it's hard to imagine a better one for the iPod. (And yes, as far as I can tell, this is completely legit.)

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

1,000 Words

Tuesday, July 25, 2006

Signing Statements

Finally, attention is being paid. Some months ago I started reading articles talking about President Bush's use of signing statements when a bill comes before him to be signed into law. A signing statement, as traditionally used by previous presidents, is designed to record a president's understanding of a new law so that, in any future disputes over that law's purpose and execution, his point of view can be considered together with that of the Congress. An excellent FindLaw column written by Jennifer Van Bergen talks about the history and purpose of these signing statements, noting that in two major cases the Supreme Court has in fact relied in part on presidential signing statements in their consideration of the laws involved.

But yesterday, the American Bar Association issued a report declaring that President Bush's signing statements are violations of the Constitution, and Senator Arlen Spector yesterday announced that he is introducing a bill that will "authorize the Congress to undertake judicial review of those signing statements with the view to having the president's acts declared unconstitutional." The question arises: why are people getting fidgety about these signing statements now, when they've been used since the Monroe administration? What has changed? Are Mr. Bush's opponents simply latching onto a new way to attack him? Or is there something new in the way Mr. Bush uses these signing statements that raises serious constitutional issues? In my view--and that of the ABA and Senator Spector and FindLaw's Ms. Van Bergen--it's the latter.

In our social studies classes, we all get taught the basic catechism of the U.S. separation of powers: the Legislative branch creates the law, the Executive branch enforces the law, and the Judicial branch interprets the law. (As Ms. Van Bergen notes, the idea of "judicial supremacy" has been in place ever since the famous Marbury v. Madison decision in 1803, when Justice Marshall wrote that "It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is."

But President Bush's signing statements have routinely crossed the line between "just so you know, this is what I think this new law means" into "the hell with you, this law means what I say it means." The Boston Globe ran an excellent list of examples of Bush's signing statements, first summarizing the law as written by Congress and then the import of the President's signing statement. Very often, the signing statement reads like a letter from the Bizarro world. For example, in December 2005, John McCain managed to push through legislation declaring that U.S. interrogators cannot torture prisoners. It was very plainly a reaction to the ongoing revelations about interrogation procedures at Abu Ghraib, Guantanomo Bay and elsewhere. In his signing statement, Bush simply declared that if he determines that "harsh interrogation" might help prevent a terror attack, then he will authorize it. The plain will of the Congress was simply up-ended. The President baldly declared that he will enforce the law except when he doesn't feel like it. With that, more than two hundred years of Constitutional precedent got tossed out the window.

The White House tries to insist that Bush's use of signing statements has been in keeping with presidential precedent, but they never get specific. White House spokesman Tony Snow said recently, "A great many of those signing statements may have little statements about questions about constitutionality. It never says, 'We're not going to enact the law.'" But how else is one to read Bush's declaration that he will direct the torture of a prisoner if he feels it might further the always-vague war against terror? And as far as I know, no one from the White House has ever produced a signing statement from any previous president that went as far in baldly reinterpreting the law.

As always, what will happen is this: a court challenge will arise as to one or another of these signing statements, and Bush administration officials will claim that they consulted with the office of the White House counsel, or with the Justice Department, and that Alberto "Lapdog" Gonzalez or some other lawyer said it was okay. This allows them to claim they were acting in good faith and that, if the Supreme Court declares a particular signing statement to be unconstitutional, well then so be it, and ain't it nice that now everybody's on the same page. (This was exactly their response to the recent Hamdan decision concerning military tribunals.)

By that thinking, as long as a president can get any of his lawyers to claim they were acting in good faith, then a president can never do anything wrong. Never. Signing statements have become, in effect, a kind of substitute for the line-item veto, except that they aren't being used to remove frivolous budgetary items, they're being consistently used to accrue more power to the Executive branch and to abridge the civil rights of you and me and everybody. They are perhaps the most egregious of President Bush's crimes against the body politic, and it's bloody well about time that the ABA and Sen. Spector and others have started to howl.

But yesterday, the American Bar Association issued a report declaring that President Bush's signing statements are violations of the Constitution, and Senator Arlen Spector yesterday announced that he is introducing a bill that will "authorize the Congress to undertake judicial review of those signing statements with the view to having the president's acts declared unconstitutional." The question arises: why are people getting fidgety about these signing statements now, when they've been used since the Monroe administration? What has changed? Are Mr. Bush's opponents simply latching onto a new way to attack him? Or is there something new in the way Mr. Bush uses these signing statements that raises serious constitutional issues? In my view--and that of the ABA and Senator Spector and FindLaw's Ms. Van Bergen--it's the latter.

In our social studies classes, we all get taught the basic catechism of the U.S. separation of powers: the Legislative branch creates the law, the Executive branch enforces the law, and the Judicial branch interprets the law. (As Ms. Van Bergen notes, the idea of "judicial supremacy" has been in place ever since the famous Marbury v. Madison decision in 1803, when Justice Marshall wrote that "It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is."

But President Bush's signing statements have routinely crossed the line between "just so you know, this is what I think this new law means" into "the hell with you, this law means what I say it means." The Boston Globe ran an excellent list of examples of Bush's signing statements, first summarizing the law as written by Congress and then the import of the President's signing statement. Very often, the signing statement reads like a letter from the Bizarro world. For example, in December 2005, John McCain managed to push through legislation declaring that U.S. interrogators cannot torture prisoners. It was very plainly a reaction to the ongoing revelations about interrogation procedures at Abu Ghraib, Guantanomo Bay and elsewhere. In his signing statement, Bush simply declared that if he determines that "harsh interrogation" might help prevent a terror attack, then he will authorize it. The plain will of the Congress was simply up-ended. The President baldly declared that he will enforce the law except when he doesn't feel like it. With that, more than two hundred years of Constitutional precedent got tossed out the window.

The White House tries to insist that Bush's use of signing statements has been in keeping with presidential precedent, but they never get specific. White House spokesman Tony Snow said recently, "A great many of those signing statements may have little statements about questions about constitutionality. It never says, 'We're not going to enact the law.'" But how else is one to read Bush's declaration that he will direct the torture of a prisoner if he feels it might further the always-vague war against terror? And as far as I know, no one from the White House has ever produced a signing statement from any previous president that went as far in baldly reinterpreting the law.

As always, what will happen is this: a court challenge will arise as to one or another of these signing statements, and Bush administration officials will claim that they consulted with the office of the White House counsel, or with the Justice Department, and that Alberto "Lapdog" Gonzalez or some other lawyer said it was okay. This allows them to claim they were acting in good faith and that, if the Supreme Court declares a particular signing statement to be unconstitutional, well then so be it, and ain't it nice that now everybody's on the same page. (This was exactly their response to the recent Hamdan decision concerning military tribunals.)

By that thinking, as long as a president can get any of his lawyers to claim they were acting in good faith, then a president can never do anything wrong. Never. Signing statements have become, in effect, a kind of substitute for the line-item veto, except that they aren't being used to remove frivolous budgetary items, they're being consistently used to accrue more power to the Executive branch and to abridge the civil rights of you and me and everybody. They are perhaps the most egregious of President Bush's crimes against the body politic, and it's bloody well about time that the ABA and Sen. Spector and others have started to howl.

Monday, July 24, 2006

Scariest Baby Ever

Just as a follow-up, I was looking around the West L.A. Police Department's site, and came across this description of a car-theft suspect:

Now if only someone had gotten a picture....

A citizen observed a male Hispanic, Black hair, 600 feet, 225 pounds, approx 3 years old.

Now if only someone had gotten a picture....

A Little Bit of Egg in the Night

I was out for my walk, in the (relative) cool of the evening, around 10:30 last night. The police were out, in front of a home, with an ambulance as well, and as I walked past I heard a homeowner saying something about a man who "spoke perfect English" but wrote something or other in Spanish. I heard no more and kept walking on because I'm just not one of those looky-loos who have to stop and luxuriate in the fact that something bad happened to someone else. (A little further on, there were plenty of other homeowners lurking behind half-opens doors, peering through.) And I was just about home, just reaching an intersection that would leave me only a block-and-a-half away.

That's when something hit me on the shoulder. Something damned hard, yet with some give to it. Took a second to put it all together, to realize that someone in that car speeding past had thrown something at me, had thrown an egg at me. And by the time I had all that worked out, the car was already well past, without sufficient street lighting for me to even tell what kind of car it was, let alone its license plate number.

My shirt was wet with egg yolk, but it had been a glancing blow, and most of the egg was on the sidewalk a little beyond me. Still, it had been a surprisingly heavy hit; kinetically speaking, the egg had all the energy of a moving car behind it, plus added energy from a not-bad throw. I was very glad that I hadn't been hit in the face, because that would have hurt like hell.

A passer-by simply shrugged and turned the corner, plainly glad that it hadn't happened to him. (And if I hadn't been just reaching that corner, it absolutely would have been him 'cause he was the next one down the road.) I followed the tail lights of the car until it turned at an intersection a little too far away, and disappeared. And then I stood there like an idiot for a long time, hoping they might come 'round looking for new victims, in the vain hope that I might be able to somehow Get Them with better warning this time. Nothing happened, and I went home to soak my shirt.

Big red welt on the shoulder, nicely egg-shaped; it has lingered, and was still there this morning. Friends tell me I ought to be go to the police and report the incident, just in case my eggsailants were making a night of it. I'm still undecided on that; I'm at work now, and there's a meeting about the movie at 7:00 so I'm not sure when I would have time to wander over to the police station.

I called my 21 year old brother this afternoon to ask him if he had ever done anything like that. Not that it would affect my opinion of him; but if he ever had, when younger and stupider, I was hoping that maybe he might have some insight on the psychology of such a thing. Because I was never that kind of a teenager, I never got my kicks from causing random harm to strangers. Bullying never appealed to me either, probably because I got bullied so often.

It was too dark to see who was in that car. But I think anyone hearing the story automatically assumes they were teenaged boys because who else would think egging someone was funny? (Unless they were dairy terrorists....) I can just picture it, like a movie scene: one guy driving, the other sitting in the passenger seat with a carton of eggs open in his lap. One egg at the ready in his hand, and maybe there's already been one try that missed. Then a new opportunity, just appearing at an intersection, no time to aim, he just had to trust his instinct. It hit, he heard me yell something profane, then he and his buddy high-fived as they sped away. "Dude, that was awesome!"

Of course, it ain't awesome. It's the sort of thing that just makes people angry, and there's way too much anger in the world already. Lord knows how pissed off I still am; it's all I can do to restrain myself from using some really foul language about these two kids and teenaged boys in particular. I'm not a public figure, this wasn't a political statement like the eggings of Bill Clinton or Arnold Schwarzenegger. This was just random mayhem, the attempted humiliation of someone just to make them feel powerful. It is axiomatic that really the opposite occurs: a drive-by egging is pure cowardice; real power would be daring to go up to someone face-to-face, but that would surely make these young louts piss their pants.

When I asked my brother whether he'd ever egged anyone, he said he never had. That once, when he was five and washing the cars with Dad, some neighbors drove by and he turned the hose on them. And Dad gave him such a clout to the back of his head that he never ever considered doing any such thing to anyone ever again. "Huh," I said. "Well let's hear it for corporal punishment."

Damn straight.

That's when something hit me on the shoulder. Something damned hard, yet with some give to it. Took a second to put it all together, to realize that someone in that car speeding past had thrown something at me, had thrown an egg at me. And by the time I had all that worked out, the car was already well past, without sufficient street lighting for me to even tell what kind of car it was, let alone its license plate number.

My shirt was wet with egg yolk, but it had been a glancing blow, and most of the egg was on the sidewalk a little beyond me. Still, it had been a surprisingly heavy hit; kinetically speaking, the egg had all the energy of a moving car behind it, plus added energy from a not-bad throw. I was very glad that I hadn't been hit in the face, because that would have hurt like hell.

A passer-by simply shrugged and turned the corner, plainly glad that it hadn't happened to him. (And if I hadn't been just reaching that corner, it absolutely would have been him 'cause he was the next one down the road.) I followed the tail lights of the car until it turned at an intersection a little too far away, and disappeared. And then I stood there like an idiot for a long time, hoping they might come 'round looking for new victims, in the vain hope that I might be able to somehow Get Them with better warning this time. Nothing happened, and I went home to soak my shirt.

Big red welt on the shoulder, nicely egg-shaped; it has lingered, and was still there this morning. Friends tell me I ought to be go to the police and report the incident, just in case my eggsailants were making a night of it. I'm still undecided on that; I'm at work now, and there's a meeting about the movie at 7:00 so I'm not sure when I would have time to wander over to the police station.

I called my 21 year old brother this afternoon to ask him if he had ever done anything like that. Not that it would affect my opinion of him; but if he ever had, when younger and stupider, I was hoping that maybe he might have some insight on the psychology of such a thing. Because I was never that kind of a teenager, I never got my kicks from causing random harm to strangers. Bullying never appealed to me either, probably because I got bullied so often.

It was too dark to see who was in that car. But I think anyone hearing the story automatically assumes they were teenaged boys because who else would think egging someone was funny? (Unless they were dairy terrorists....) I can just picture it, like a movie scene: one guy driving, the other sitting in the passenger seat with a carton of eggs open in his lap. One egg at the ready in his hand, and maybe there's already been one try that missed. Then a new opportunity, just appearing at an intersection, no time to aim, he just had to trust his instinct. It hit, he heard me yell something profane, then he and his buddy high-fived as they sped away. "Dude, that was awesome!"

Of course, it ain't awesome. It's the sort of thing that just makes people angry, and there's way too much anger in the world already. Lord knows how pissed off I still am; it's all I can do to restrain myself from using some really foul language about these two kids and teenaged boys in particular. I'm not a public figure, this wasn't a political statement like the eggings of Bill Clinton or Arnold Schwarzenegger. This was just random mayhem, the attempted humiliation of someone just to make them feel powerful. It is axiomatic that really the opposite occurs: a drive-by egging is pure cowardice; real power would be daring to go up to someone face-to-face, but that would surely make these young louts piss their pants.

When I asked my brother whether he'd ever egged anyone, he said he never had. That once, when he was five and washing the cars with Dad, some neighbors drove by and he turned the hose on them. And Dad gave him such a clout to the back of his head that he never ever considered doing any such thing to anyone ever again. "Huh," I said. "Well let's hear it for corporal punishment."

Damn straight.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

The Media Starts to Catch Up

Melissa McNamara with CBS News quoted me the other day in her blog-roundup article called "Blogophile," talking about the poor guy who mistook an Onion article for real news. Which is very cool, and I just wanted to mention it for all three of you who are regular readers.

The Poverty Trap

In Signal to Noise, Marc and I wrote a scene in which a film director, during a Q&A with audience members, poses a question to them: "What's the purpose of film?" he asks. After a little back-and-forth, he finally says something like "The purpose of film is to make you feel. If it also teaches you something, well, that's gravy."

The other night I watched City of God, the spectacular film from Brazil directed by Fernando Meirelles and Katia Lund. Because I sometimes do things backward, I had already seen (and admired) Mereilles's follow-up film, The Constant Gardener; finally I got around to this earlier film, and thought it was fantastic. But on the DVD there is also a documentary titled "News From a Personal War," and by the time I had finished watching everything my head was spinning.

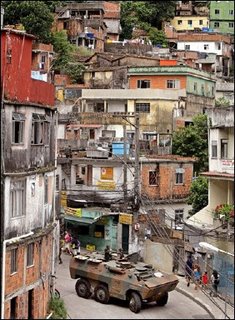

The movie and documentary focus on the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, the horrific slums that are so bad they have become societies unto themselves where only the police dare venture, heavily armed and in numbers. As the favelas grew shack-by-shack, outside of commercial or governmental development plans, usually there is no plumbing, no electricity, no phones. One character in the film mentions that he has never taken a hot bath in his life--and because the actors were non-professionals recruited directly from the favelas, that happened to be a real comment that the camera managed to capture.

What was most fascinating, though, was the society that grew up within this awful poverty. Drugs provide the capital, and plenty of it: middle-class Brazilians pay good money to feed their coke habits, and that money travels up the hillsides into Rocinha or Cidade de Deus and become the basis for a new society, with the druglords at its head. The documentary featured several residents telling about the essential services provided by the druglords: if someone's shack needs repairs, or a family needs furniture, or a resident needs new shoes, or a family needs a funeral, they come to the druglords and are given money to take care of things. When a druglord's territory is well-established, a very real peace will settle onto that territory, as random crimes are suppressed and folded into the larger efforts of the druglords. Only when territorial disputes erupt does major violence flare up, though at these times the violence is very bad indeed.

Teenaged members of the crime gangs were interviewed for the documentary, each one a perfect fatalist. Life expectancy is about 25 years, and several of the young men interviewed expressed some variation of the "We all die sometime" mantra, using that to justify a life in which absolutely anything goes so long as it serves their private needs. Murder is just part of a day at the office, essentially; indeed, in one startling juxtaposition in the documentary, a young gang member talks about how his first murder really didn't trouble him at all, then the film cut to a policeman who said exactly the same thing about the people he has had to shoot in his quasi-military engagements in the favelas.

It didn't take long for me to begin noticing some patterns in the favelas that also play out in the rest of the world. Why, for example, did Hamas win seats in the Palestinian parliament? Because Hamas has for a long time been providing school and medical facilities for the impoverished people of the territories, filling a need that the established authority, the PLO, had ignored or been unable to provide for. The same is true of Hezbollah in the south of Lebanon, and we see the results playing out in news reports every day now: these well-armed militias have so become a part of daily life in these areas that they are heroes to the people, and the established authority--be it an invading Israeli army or the nearly-impotent government of Lebanon--are an enemy to be defeated. With the same lack of remorse that characterizes the young hoodlums of the favelas.

This is true in Iraq, where the militias of Muqtada al-Sadr and others are largely responsible for the brewing civil war, and in Somalia, where the Taliban-styled Islamist militias have now almost entirely succeeded in ousting the "real" government. How do you think the Taliban was able to take over Afganistan in the first place? The riots in France last year had a lot to do with immigrants suffering from societal poverty who felt they had no option but to rise up against a new set of laws that would have made their lives even worse. And Columbia has essentially belonged to the drug kingpins for decades now.

Obviously, yes, I know: I'm hardly the first person to discover that poverty and economic inequality are big honkin' problems the wide world over (hello, Marx and Engels!). But there's a difference between understanding a thing intellectually, as a thing you recognize from having read some books, and that moment when suddenly you see it all laid out, each link in place, and the pattern becomes clear. For every person, that moment is always individual and distinct. For me, the combination of City of God, the documentary that accompanies it on the DVD, and the hundreds of news reports over the last several years, created that moment: link to link, the whole chain of poverty and its awful effects, wrapping itself around the world.

After all, let us not forget that there is poverty almost as bad here in the U.S. There are parts of Los Angeles where the police almost never go because it's just too dangerous, and the same is true of places like the Robert Taylor projects in Chicago or parts of Harlem. Anyone who's seen The Godfather knows that the Mafia often fills a whole range of needs in poorer communities, as do the Crips of L.A. The favelas are perhaps a step further along than we are in that line that marches from poverty to organization to rebellion, but it's worth remembering--as the differences between American haves and have-nots continues to grow and grow--that there is in fact a direct line to be drawn between poverty and the Taliban, and that if we just sit back and enjoy our comfy lives, ignoring what's going on in our own favelas, one day we might find that our comfy lives have disappeared right out from under us.

Sunday, July 16, 2006

MySpace

So a year after taking the blogging plunge and largely enjoying it, now I've done the MySpace thing. Just trying to keep current with the young people, doncha know.

I looked at MySpace a few months ago and just didn't like it. The pages were too cluttered, there was too much stuff all over the place and it didn't seem like anything led to anything except more of the same. All the chaos of modern life, dumped onto endless web pages. But it didn't take long to notice that, for bands at least, MySpace has been a godsend, and sometimes there is interesting music to be found. But I still wasn't terribly interested--who wants to help Rupert Murdoch when he doesn't absolutely have to? (Check here for a lovely MySpace-based parody page for Mr. Murdoch.)

But you know. Things change. And since Zen Noir is going to be in theaters starting September 15th, suddenly MySpace--and the grassroots marketing opportunity it represents--became a lot more attractive. Obviously it's just a tiny part of our marketing campaign, but for a smaller movie like ours, the grassroots end will be important. There's already a YouTube page with the trailer, and we'll be putting up a MySpace page for the movie soon.

As a kind of dry run, I set up my own page last week. And yes, the layout is definitely clunky; but it doesn't take long before you realize that you could spend hours just wandering from link to link to link. (Which is of course exactly why Mr. Murdoch was interested--look at all those ads you're absorbing!) But there is an undeniable kick from finding people on there who you'd have never expected. I looked around for a friend from college, found her, then discovered in her Friends section other people I'd known in college. So then I searched for Emerson College alumnae who attended during a certain span of years, and found several other people I knew. I could probably do the same with people from high school, actors in shows I did, and so forth.

(On the other hand, it was more than a little weird to find my little sister had put up a page reading, in part, that she wants to meet "GUYS!!!!" I mean--four exclamation points? Yikes! Wasn't she just six years old, like, yesterday?)

So all in all, even though old Rupert is profiting from it, well, so am I. And so far he hasn't tried to shove any of his Fox News viewpoint down my throat, so what do I have to complain about? Now if I could just figure out how people are managing to customize their pages, that would be very nice.

I looked at MySpace a few months ago and just didn't like it. The pages were too cluttered, there was too much stuff all over the place and it didn't seem like anything led to anything except more of the same. All the chaos of modern life, dumped onto endless web pages. But it didn't take long to notice that, for bands at least, MySpace has been a godsend, and sometimes there is interesting music to be found. But I still wasn't terribly interested--who wants to help Rupert Murdoch when he doesn't absolutely have to? (Check here for a lovely MySpace-based parody page for Mr. Murdoch.)

But you know. Things change. And since Zen Noir is going to be in theaters starting September 15th, suddenly MySpace--and the grassroots marketing opportunity it represents--became a lot more attractive. Obviously it's just a tiny part of our marketing campaign, but for a smaller movie like ours, the grassroots end will be important. There's already a YouTube page with the trailer, and we'll be putting up a MySpace page for the movie soon.

As a kind of dry run, I set up my own page last week. And yes, the layout is definitely clunky; but it doesn't take long before you realize that you could spend hours just wandering from link to link to link. (Which is of course exactly why Mr. Murdoch was interested--look at all those ads you're absorbing!) But there is an undeniable kick from finding people on there who you'd have never expected. I looked around for a friend from college, found her, then discovered in her Friends section other people I'd known in college. So then I searched for Emerson College alumnae who attended during a certain span of years, and found several other people I knew. I could probably do the same with people from high school, actors in shows I did, and so forth.

(On the other hand, it was more than a little weird to find my little sister had put up a page reading, in part, that she wants to meet "GUYS!!!!" I mean--four exclamation points? Yikes! Wasn't she just six years old, like, yesterday?)

So all in all, even though old Rupert is profiting from it, well, so am I. And so far he hasn't tried to shove any of his Fox News viewpoint down my throat, so what do I have to complain about? Now if I could just figure out how people are managing to customize their pages, that would be very nice.

Friday, July 14, 2006

Ah, Satire

Apparently I'm not the only person who looked at the news yesterday and reacted with alarm. Over at Salon, their War Room columnist had almost exactly the same take on it all, with better detail; while on The Daily Show, Jon Stewart wrestled with the thorny problem of finding humor in the beginning of "World War III," and solved the problem with Jason Jones's beautiful "Emotional Weatherman" segment, featuring "Shrapnel the Despair Penguin."

Meanwhile, also on Salon today was Rebecca Traister's report on a guy named Pete, an anti-abortion activist who made the unfortunate mistake of taking an Onion story seriously. Liberal bloggers went all crazy-like and have been making fun of the guy all week, and really, how can you not? Trouble is, it's too easy a target. And we all get fooled from time to time, and it's really gonna suck when one of "us" gets something wrong and is mocked across the worldwide web for days on end.

Sure: Pete didn't understand that the piece was satire. A lot of folks didn't quite understand that Jonathan Swift was kidding when he suggested the Irish eat their children, too. That's one of the reasons why we like satire: every once in a while someone doesn't quite get the joke, and then we can have the fun of explaining it to them. It may kill the humor, but it still gets the point across.

Which is one of the things our man Pete still isn't quite getting. In attempting to defend himself, which he (mostly) did with an admirable sense of humor about the whole thing, he asserted at one point "Do you see how they slip their agenda into a 'satirical' piece?" His point was that this piece of humor still had an agenda, which again reflects a complete misunderstanding of satire. Of course it has an agenda--that's the whole point. Satire is really just another weapon in the arsenal of argumentation and, as has been proved time and again by Mark Twain, Bernard Shaw, Stephen Colbert and a host of others, very often this humor-with-a-hook is the most effective way of making a point. The hook catches and sticks, the entertainment of the humor wins you over and then suddenly you realize what you've been won over to.

(By the way, I never commented on Colbert's Correspondent Association speech, but it was brilliant, and all the more delightful for being done right in the face of the President, and it's well worth watching the whole thing.)

But. Let's leave poor old Pete alone, shall we? As Ms. Traister notes, a lot of the reactions in the blogosphere have been just plain insulting; and calls to the man's house are way over the line. The guy made a mistake, and he happens to be on the other side of the ideological line; but I'm telling you, it's awful tough to take the moral high ground on things when you're calling some guy's house just to abuse him. That's a shitty way to make a point, and it only works against the point you're trying to make by causing others to write you off as just another asshole liberal. In other words, you can't get all highfalutin' about Dick Cheney being an asshole if you're an asshole too. So let's just get off Pete's back and get back to business. Enough is enough.

Okay, not quite enough. My favorite bit in the whole thing? It's Ms. Traister's very last paragraph, where Pete suggests that because he grew up in Germany, where the natives famously lack a sense of humor, he has been a complete sucker for satire all his life. Now that's effin' hilarious.

Meanwhile, also on Salon today was Rebecca Traister's report on a guy named Pete, an anti-abortion activist who made the unfortunate mistake of taking an Onion story seriously. Liberal bloggers went all crazy-like and have been making fun of the guy all week, and really, how can you not? Trouble is, it's too easy a target. And we all get fooled from time to time, and it's really gonna suck when one of "us" gets something wrong and is mocked across the worldwide web for days on end.

Sure: Pete didn't understand that the piece was satire. A lot of folks didn't quite understand that Jonathan Swift was kidding when he suggested the Irish eat their children, too. That's one of the reasons why we like satire: every once in a while someone doesn't quite get the joke, and then we can have the fun of explaining it to them. It may kill the humor, but it still gets the point across.