In Signal to Noise, Marc and I wrote a scene in which a film director, during a Q&A with audience members, poses a question to them: "What's the purpose of film?" he asks. After a little back-and-forth, he finally says something like "The purpose of film is to make you feel. If it also teaches you something, well, that's gravy."

The other night I watched City of God, the spectacular film from Brazil directed by Fernando Meirelles and Katia Lund. Because I sometimes do things backward, I had already seen (and admired) Mereilles's follow-up film, The Constant Gardener; finally I got around to this earlier film, and thought it was fantastic. But on the DVD there is also a documentary titled "News From a Personal War," and by the time I had finished watching everything my head was spinning.

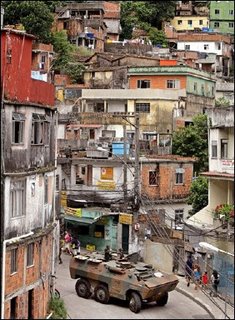

The movie and documentary focus on the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, the horrific slums that are so bad they have become societies unto themselves where only the police dare venture, heavily armed and in numbers. As the favelas grew shack-by-shack, outside of commercial or governmental development plans, usually there is no plumbing, no electricity, no phones. One character in the film mentions that he has never taken a hot bath in his life--and because the actors were non-professionals recruited directly from the favelas, that happened to be a real comment that the camera managed to capture.

What was most fascinating, though, was the society that grew up within this awful poverty. Drugs provide the capital, and plenty of it: middle-class Brazilians pay good money to feed their coke habits, and that money travels up the hillsides into Rocinha or Cidade de Deus and become the basis for a new society, with the druglords at its head. The documentary featured several residents telling about the essential services provided by the druglords: if someone's shack needs repairs, or a family needs furniture, or a resident needs new shoes, or a family needs a funeral, they come to the druglords and are given money to take care of things. When a druglord's territory is well-established, a very real peace will settle onto that territory, as random crimes are suppressed and folded into the larger efforts of the druglords. Only when territorial disputes erupt does major violence flare up, though at these times the violence is very bad indeed.

Teenaged members of the crime gangs were interviewed for the documentary, each one a perfect fatalist. Life expectancy is about 25 years, and several of the young men interviewed expressed some variation of the "We all die sometime" mantra, using that to justify a life in which absolutely anything goes so long as it serves their private needs. Murder is just part of a day at the office, essentially; indeed, in one startling juxtaposition in the documentary, a young gang member talks about how his first murder really didn't trouble him at all, then the film cut to a policeman who said exactly the same thing about the people he has had to shoot in his quasi-military engagements in the favelas.

It didn't take long for me to begin noticing some patterns in the favelas that also play out in the rest of the world. Why, for example, did Hamas win seats in the Palestinian parliament? Because Hamas has for a long time been providing school and medical facilities for the impoverished people of the territories, filling a need that the established authority, the PLO, had ignored or been unable to provide for. The same is true of Hezbollah in the south of Lebanon, and we see the results playing out in news reports every day now: these well-armed militias have so become a part of daily life in these areas that they are heroes to the people, and the established authority--be it an invading Israeli army or the nearly-impotent government of Lebanon--are an enemy to be defeated. With the same lack of remorse that characterizes the young hoodlums of the favelas.

This is true in Iraq, where the militias of Muqtada al-Sadr and others are largely responsible for the brewing civil war, and in Somalia, where the Taliban-styled Islamist militias have now almost entirely succeeded in ousting the "real" government. How do you think the Taliban was able to take over Afganistan in the first place? The riots in France last year had a lot to do with immigrants suffering from societal poverty who felt they had no option but to rise up against a new set of laws that would have made their lives even worse. And Columbia has essentially belonged to the drug kingpins for decades now.

Obviously, yes, I know: I'm hardly the first person to discover that poverty and economic inequality are big honkin' problems the wide world over (hello, Marx and Engels!). But there's a difference between understanding a thing intellectually, as a thing you recognize from having read some books, and that moment when suddenly you see it all laid out, each link in place, and the pattern becomes clear. For every person, that moment is always individual and distinct. For me, the combination of City of God, the documentary that accompanies it on the DVD, and the hundreds of news reports over the last several years, created that moment: link to link, the whole chain of poverty and its awful effects, wrapping itself around the world.

After all, let us not forget that there is poverty almost as bad here in the U.S. There are parts of Los Angeles where the police almost never go because it's just too dangerous, and the same is true of places like the Robert Taylor projects in Chicago or parts of Harlem. Anyone who's seen The Godfather knows that the Mafia often fills a whole range of needs in poorer communities, as do the Crips of L.A. The favelas are perhaps a step further along than we are in that line that marches from poverty to organization to rebellion, but it's worth remembering--as the differences between American haves and have-nots continues to grow and grow--that there is in fact a direct line to be drawn between poverty and the Taliban, and that if we just sit back and enjoy our comfy lives, ignoring what's going on in our own favelas, one day we might find that our comfy lives have disappeared right out from under us.

No comments:

Post a Comment