Okay, you can't fool me. Call it "anecdotal evidence" all you want, but I know the truth through the scientific method. First, you see, you observe something that seems to be a pattern, and from it you devise a theory. Then you test that theory over time, to see if it holds up. Through this, I have cleverly deduced one of the great unknown conspiracies:

The batteries in smoke detectors have little timers built in so that they will always start to die between 1:00 and 4:00 in the morning, thus waking people up when they start to chirp very loudly and making the general populace tired, cranky and iiritable. (And, apparently, unable to spell.)

As I'm sure you know, most good smoke detectors these days are wired into building power, and this is a good thing--but you always want them to have battery backups, because if the fire takes out building power, you don't want to lose your smoke detector at that very critical moment. Batteries are, therefore, a good thing. But you know how it always works out: the battery starts to go, and the smoke detector is programmed to start chirping so that you know to replace the battery and keep yourself from, you know, burning to death in a fire. But I'll bet you've observed it, too: the chirping only ever starts at some godawful hour of the morning. And "chirp" is the gentle way of describing a most ungentle sound.

Now one might be inclined to think this is all just coincidence, until you climb out of bed and try to remove the battery. The one I wrestled with last night was plugged into the wall through a plug that held tight like a squid with a bottle of fish in its tentacles. Plus it had this little tab that extended right over the battery compartment--you simply could not change the battery without first unplugging the unit, which was kinda sorta impossible. Plus there's the fact that the smoke detector is high up on a wall, and if I were something less than 6'3" it would've been pretty well impossible.

By this point, I was really incredibly awake.

Eventually a pair of pliers did the trick, though I'm amazed I didn't destroy the unit in the process. And now the unit sits on a counter, unplugged and unbatteried, and I'd better hope a fire doesn't start near the front door in the next few hours or I'm toast.

Insult to injury: even after you've removed the battery, the damn thing still retains a charge for a while. It still chirps. Larry David had enormous fun with this in the first episode of the new season of Curb Your Enthusiasm, and of course I watched and laughed and then, not two weeks later, lived through the same scene in real time.

But I just wanted to, you know, warn people. About this great conspiracy. Now let us all turn our attentions to the pernicious question of why.

Sunday, September 23, 2007

Saturday, September 08, 2007

Is It Progress?

I have now owned a guitar for two weeks, and I have been practicing at least a little bit every day. And so far...

...well, so far I still suck.

See, the frustrating part is that it's such a huge thing to learn because the guitar is more flexible than I'd realized. Chord fingerings for the left hand to learn, and not just a few of them--I've seen chord books for sale that advertise "1,000 chords diagrammed!" The techniques of strumming and picking for the right hand. The infinitely tricky separation of the right hand from the left hand. Learning to read tablature. Learning to read chord charts. Learning to read musical notation. A metronome to keep me on track rhythmically. Not to mention the necessity of actual physical changes that are required: the growth of callouses on the fingertips of the left hand so that there isn't so much, you know, pain when I play. ("I got blisters on my fingers!" shouted John, and now I get why.)

But it's been two weeks, and I've been practicing regularly, and I've learned to play five of the principal chords (A, C, D, E and G) pretty well. There are a couple very simple melodies (played on just two strings, involving only three frets) that I can now make my way through decently. I can sit down with tablature or a chord chart and work it through, slowly, but I can do it. But that's about it.

I still can't put any of those five chords together--I've been trying for days now to shift from A to D and back again, and although I'm slightly better than when I started, it's still pretty horrible. (The fingers just keep ending up in bad places for the D chord, and when I try to play it at speed I always get at least one dead string and another one buzzing badly.) Considering that this shift from A to D is part of only Lesson 2 of a course I'm taking, it feels pretty discouraging.

But perhaps part of the problem is that I'm trying too many things at once. When I purchased the guitar I bought a DVD and book for the Hal Leonard method. And while I like the book, the DVD jumped almost immediately into reading notation on staves, at which I am really terrible. So I poked around on the internet and found a course almost universally recommended called Jamorama, put together by a New Zealander named Ben Edwards, and it only cost $40 so I bought it. And I definitely like it, but that's the one where I'm already stuck on Lesson 2, with dozens of lessons still to go. Then I bought a book containing lots of guitar chords, along with scales and arpeggios, all nicely diagrammed, so part of my practice now involves slowly working my way through, say, the C scale.

method. And while I like the book, the DVD jumped almost immediately into reading notation on staves, at which I am really terrible. So I poked around on the internet and found a course almost universally recommended called Jamorama, put together by a New Zealander named Ben Edwards, and it only cost $40 so I bought it. And I definitely like it, but that's the one where I'm already stuck on Lesson 2, with dozens of lessons still to go. Then I bought a book containing lots of guitar chords, along with scales and arpeggios, all nicely diagrammed, so part of my practice now involves slowly working my way through, say, the C scale.

It's definitely possible, though, that all that is part of my problem. I'm doing a little out of the Hal Leonard book, a little out of Jamorama, a little scales work, and so forth. I'm not following any one course systematically, I'm trying to design a scattershot program on the fly without any idea what the hell I'm doing. Which is probably exactly why all I can see at the moment is the vastness of the task, instead of just focusing on, say, nailing the transition from the A to the D chord.

I ain't quittin' yet. No sir. I mean hey, I've got these fresh callouses on my fingertips, so that's one thing I've succeeded at. Time and repetition, and there they are, just like they're supposed to be. It would just be silly to quit now.

...well, so far I still suck.

See, the frustrating part is that it's such a huge thing to learn because the guitar is more flexible than I'd realized. Chord fingerings for the left hand to learn, and not just a few of them--I've seen chord books for sale that advertise "1,000 chords diagrammed!" The techniques of strumming and picking for the right hand. The infinitely tricky separation of the right hand from the left hand. Learning to read tablature. Learning to read chord charts. Learning to read musical notation. A metronome to keep me on track rhythmically. Not to mention the necessity of actual physical changes that are required: the growth of callouses on the fingertips of the left hand so that there isn't so much, you know, pain when I play. ("I got blisters on my fingers!" shouted John, and now I get why.)

But it's been two weeks, and I've been practicing regularly, and I've learned to play five of the principal chords (A, C, D, E and G) pretty well. There are a couple very simple melodies (played on just two strings, involving only three frets) that I can now make my way through decently. I can sit down with tablature or a chord chart and work it through, slowly, but I can do it. But that's about it.

I still can't put any of those five chords together--I've been trying for days now to shift from A to D and back again, and although I'm slightly better than when I started, it's still pretty horrible. (The fingers just keep ending up in bad places for the D chord, and when I try to play it at speed I always get at least one dead string and another one buzzing badly.) Considering that this shift from A to D is part of only Lesson 2 of a course I'm taking, it feels pretty discouraging.

But perhaps part of the problem is that I'm trying too many things at once. When I purchased the guitar I bought a DVD and book for the Hal Leonard

It's definitely possible, though, that all that is part of my problem. I'm doing a little out of the Hal Leonard book, a little out of Jamorama, a little scales work, and so forth. I'm not following any one course systematically, I'm trying to design a scattershot program on the fly without any idea what the hell I'm doing. Which is probably exactly why all I can see at the moment is the vastness of the task, instead of just focusing on, say, nailing the transition from the A to the D chord.

I ain't quittin' yet. No sir. I mean hey, I've got these fresh callouses on my fingertips, so that's one thing I've succeeded at. Time and repetition, and there they are, just like they're supposed to be. It would just be silly to quit now.

Labels:

How we learn things,

Not wafting,

The Guitar

Sunday, August 26, 2007

In Which I Acquire a Guitar

The other day, a friend of mine decided to take advantage of a pretty amazing 2-for-1 offer at West L.A. Music. He went shopping for an electric and a new acoustic, to replace the entry-level guitar he'd had for years. I went along, always happy to watch someone else spend money, but once there, I had practically nothing to do.

I play no instruments, it's just not something that comes naturally to me. I took a music theory class and found it even harder than math--this with a very good teacher, Tony Tommasini, who is now one of the classical music critics for the New York Times. I also took exactly one piano lesson from Tony (won it in an auction), who declared that I had good large hands with a long reach, but never said anything about my having any observable aptitude for the instrument. I pretty much decided it was all too hard, and let the whole thing drop. Sure, I taught myself to sing reasonably well, even did a little recording with a madrigal group, but believe me, I've heard Pavarotti sing and the man has nothing to worry about.

And yet. When you watch Inside the Actors Studio and James Liption asks his list of questions, one of them is always "If you couldn't do your current profession, what other profession would you choose?" And every time, for me, the answer is one of two: either astronomer or musician. And astronomy involves math, really ridiculously high-level math, so you know how likely that is.

So I went along on this guitar-buying excursion because I figured it was the only way I'd ever actually participate in the process of buying a guitar. And like I said, once there I had little to do because I had almost no idea what anyone was talking about. I would be asked "How's this one sound?" and I would say "Sounds pretty good" every time.

Then the next day I went out and bought a guitar of my own. Because damn it, that little trip put a bug in my head and I knew I wasn't going to be able to shake it. But hey, I've always intended, for years, maybe decades, to try to learn an instrument some day. And since I don't have a time-consuming dayjob anymore, now seemed like an ideal time.

My friend went along because honestly, I could pick up a guitar and strum it, but I was utterly unequipped to tell a good one from a bad one. (Plus he needed an amp for his new Strat.) I'd seen on the internet that Fender makes a beginner's kit with a guitar, a strap, some picks, a tuner, some extra strings, a gig bag and a DVD with some lessons on it, all for $200. Fender's a good name, it seemed like a good deal, and it was in stock at the Guitar Center in Hollywood. Off we went.

In the end I picked a guitar that wasn't part of a kit, it was simply a solid $200 Yamaha (the FG700S, in case you're curious), then I bought the other stuff separately. Took it home, and since then I've been going through the exciting, agonizing process of learning the guitar, completely from scratch.

And what can I say? I completely suck. My fingers hurt (and when I took a shower this morning, oh how they throbbed in the hot water), there are chords I can barely manage even when I spend five minutes trying to get them right, my sense of rhythm is beyond shaky, and even though it's hot I always close all the windows because if there's anything a neighbor doesn't want to hear, it's the fractured sounds of a novice guitar player wafting through the air.

No, not wafting. These sounds definitely do not waft.

But at the same time, I can now (laboriously) form four of the principal chords, and a couple days ago I couldn't have picked those chords out of a lineup. It's a start. And I know from my experience that my learning curve has always gone like this: when I first start something I am beyond terrible, and I stay that way for a frustratingly long time. Then, at some point, suddenly it all clicks, it's all just kinda there. So I'm going to keep on with this: I've spent the money, I have the time, and for years now I've had the desire.

If only there was some way to skip the whole protracted-suckiness stage and just get to a basic level of competence, that would be soooo cool.

I play no instruments, it's just not something that comes naturally to me. I took a music theory class and found it even harder than math--this with a very good teacher, Tony Tommasini, who is now one of the classical music critics for the New York Times. I also took exactly one piano lesson from Tony (won it in an auction), who declared that I had good large hands with a long reach, but never said anything about my having any observable aptitude for the instrument. I pretty much decided it was all too hard, and let the whole thing drop. Sure, I taught myself to sing reasonably well, even did a little recording with a madrigal group, but believe me, I've heard Pavarotti sing and the man has nothing to worry about.

And yet. When you watch Inside the Actors Studio and James Liption asks his list of questions, one of them is always "If you couldn't do your current profession, what other profession would you choose?" And every time, for me, the answer is one of two: either astronomer or musician. And astronomy involves math, really ridiculously high-level math, so you know how likely that is.

So I went along on this guitar-buying excursion because I figured it was the only way I'd ever actually participate in the process of buying a guitar. And like I said, once there I had little to do because I had almost no idea what anyone was talking about. I would be asked "How's this one sound?" and I would say "Sounds pretty good" every time.

Then the next day I went out and bought a guitar of my own. Because damn it, that little trip put a bug in my head and I knew I wasn't going to be able to shake it. But hey, I've always intended, for years, maybe decades, to try to learn an instrument some day. And since I don't have a time-consuming dayjob anymore, now seemed like an ideal time.

My friend went along because honestly, I could pick up a guitar and strum it, but I was utterly unequipped to tell a good one from a bad one. (Plus he needed an amp for his new Strat.) I'd seen on the internet that Fender makes a beginner's kit with a guitar, a strap, some picks, a tuner, some extra strings, a gig bag and a DVD with some lessons on it, all for $200. Fender's a good name, it seemed like a good deal, and it was in stock at the Guitar Center in Hollywood. Off we went.

In the end I picked a guitar that wasn't part of a kit, it was simply a solid $200 Yamaha (the FG700S, in case you're curious), then I bought the other stuff separately. Took it home, and since then I've been going through the exciting, agonizing process of learning the guitar, completely from scratch.

And what can I say? I completely suck. My fingers hurt (and when I took a shower this morning, oh how they throbbed in the hot water), there are chords I can barely manage even when I spend five minutes trying to get them right, my sense of rhythm is beyond shaky, and even though it's hot I always close all the windows because if there's anything a neighbor doesn't want to hear, it's the fractured sounds of a novice guitar player wafting through the air.

No, not wafting. These sounds definitely do not waft.

But at the same time, I can now (laboriously) form four of the principal chords, and a couple days ago I couldn't have picked those chords out of a lineup. It's a start. And I know from my experience that my learning curve has always gone like this: when I first start something I am beyond terrible, and I stay that way for a frustratingly long time. Then, at some point, suddenly it all clicks, it's all just kinda there. So I'm going to keep on with this: I've spent the money, I have the time, and for years now I've had the desire.

If only there was some way to skip the whole protracted-suckiness stage and just get to a basic level of competence, that would be soooo cool.

Thursday, August 23, 2007

The Big One

Very early in the morning, two weeks ago. I woke up fast, hearing a sound: my window was rattling, and it sounded like someone was trying to get in. The sort of thing that will in fact wake up anybody mighty damn fast. But there was just enough vibration working its way through the mattress that I realized: Oh, okay. Nobody's trying to get in. It's just an earthquake. Contented, I went back to bed.

The occasion was a 4.6 seismic event, 3 miles north-northwest of Chatsworth, which is to say, pretty close to where I live. (The U.S. Geological Survey's report on the event is here.) A 4.6 earthquake is a solid earthquake, but even so, not much happened. No deaths, no injuries to speak of, no real property damage. All that happened in my apartment is that an unlit candle, stuffed in a closet, tipped over. But a few days later, a friend of mine (hi, Sarah!) happened to ask me what I thought about our chances of The Big One hitting.

The Big One is a favorite topic amongst Californians, for obvious reasons. As John McPhee details in his wonderful book Assembling California (collected with two other books in the wonderful Annals of the Former World--and by the way, I think McPhee is an incredible writer, and I would happily read his writing on any subject under the sun), the state of California was put together in pieces over millions of years. (The great central valley, for instance, is a huge hinge--two gigantic slabs of earth at angles, forming a huge V, into which sediment has slowly filled and filled the V and thus created that massive flat plain between two mountain ridges.) You've got the Pacific Plate over here, pushing against the continental plate over here, plus a smaller plate (the Juan de Fuca) to the north, and it's all inherently unstable. Big earthquakes are, in a word, inevitable.

Annals of the Former World--and by the way, I think McPhee is an incredible writer, and I would happily read his writing on any subject under the sun), the state of California was put together in pieces over millions of years. (The great central valley, for instance, is a huge hinge--two gigantic slabs of earth at angles, forming a huge V, into which sediment has slowly filled and filled the V and thus created that massive flat plain between two mountain ridges.) You've got the Pacific Plate over here, pushing against the continental plate over here, plus a smaller plate (the Juan de Fuca) to the north, and it's all inherently unstable. Big earthquakes are, in a word, inevitable.

But precisely because of my reading of Mr. McPhee, I have a remarkably casual outlook toward The Big One. Yes, it's gonna happen. Will it happen in my lifetime? No, probably not. So I just don't worry about it. This is because of an idea called "deep time."

We could call it geologic time as well. For a geologist, a million years is the smallest unit of time s/he cares about. That's how long it takes for any geologic change to happen. And once you start thinking in terms of deep time, your perspective starts to shift like crazy. Here's an example of why: look at a ruler. At the far left you have the first black marking, the Zero line. If you consider the ruler as a timeline of earth's entire geologic history, the entire span of human history wouldn't get past the Zero line. It's that small.

So if you then consider my individual lifetime against the entire span of human history, well, that's so small it simply doesn't show up on that ruler at all. That's deep time. Which means that yeah, a gigantic earthquake in my neighborhood is inevitable; these faults will one day rupture and California will one day break apart just as it formed, in pieces, separating and then drifting away toward future collisions and reconfigurations. But the chance of the first part of that chain, a major event on the San Andreas fault, happening in my lifetime is so small that I just don't see any point in worrying about it.

Think about it this way: there are no guarantees in life. None. There's no guarantee that the sun will rise in the morning tomorrow--there's only the probability that it will. Based on what we have observed in the past, there is an extremely high probability that in the morning, there it will be, the sun, shining forth as usual. We all go to sleep at night perfectly content that the odds are in our favor on this one. Well, I have the same attitude toward The Big One.

Then again--there was a small earthquake maybe two years ago, when I was at work, in Santa Monica. At the time I happened to be on my lunch break, sitting in the lobby of the building with a book in my hand. I felt the ground jump a little and then looked up--to realize that I was sitting in a glass-roofed extension of the lobby, and that these gigantic panes of glass were shivering above me.

And yeah, I'm not crazy--that made me a little nervous.

The occasion was a 4.6 seismic event, 3 miles north-northwest of Chatsworth, which is to say, pretty close to where I live. (The U.S. Geological Survey's report on the event is here.) A 4.6 earthquake is a solid earthquake, but even so, not much happened. No deaths, no injuries to speak of, no real property damage. All that happened in my apartment is that an unlit candle, stuffed in a closet, tipped over. But a few days later, a friend of mine (hi, Sarah!) happened to ask me what I thought about our chances of The Big One hitting.

The Big One is a favorite topic amongst Californians, for obvious reasons. As John McPhee details in his wonderful book Assembling California (collected with two other books in the wonderful

Annals of the Former World--and by the way, I think McPhee is an incredible writer, and I would happily read his writing on any subject under the sun), the state of California was put together in pieces over millions of years. (The great central valley, for instance, is a huge hinge--two gigantic slabs of earth at angles, forming a huge V, into which sediment has slowly filled and filled the V and thus created that massive flat plain between two mountain ridges.) You've got the Pacific Plate over here, pushing against the continental plate over here, plus a smaller plate (the Juan de Fuca) to the north, and it's all inherently unstable. Big earthquakes are, in a word, inevitable.

Annals of the Former World--and by the way, I think McPhee is an incredible writer, and I would happily read his writing on any subject under the sun), the state of California was put together in pieces over millions of years. (The great central valley, for instance, is a huge hinge--two gigantic slabs of earth at angles, forming a huge V, into which sediment has slowly filled and filled the V and thus created that massive flat plain between two mountain ridges.) You've got the Pacific Plate over here, pushing against the continental plate over here, plus a smaller plate (the Juan de Fuca) to the north, and it's all inherently unstable. Big earthquakes are, in a word, inevitable.But precisely because of my reading of Mr. McPhee, I have a remarkably casual outlook toward The Big One. Yes, it's gonna happen. Will it happen in my lifetime? No, probably not. So I just don't worry about it. This is because of an idea called "deep time."

We could call it geologic time as well. For a geologist, a million years is the smallest unit of time s/he cares about. That's how long it takes for any geologic change to happen. And once you start thinking in terms of deep time, your perspective starts to shift like crazy. Here's an example of why: look at a ruler. At the far left you have the first black marking, the Zero line. If you consider the ruler as a timeline of earth's entire geologic history, the entire span of human history wouldn't get past the Zero line. It's that small.

So if you then consider my individual lifetime against the entire span of human history, well, that's so small it simply doesn't show up on that ruler at all. That's deep time. Which means that yeah, a gigantic earthquake in my neighborhood is inevitable; these faults will one day rupture and California will one day break apart just as it formed, in pieces, separating and then drifting away toward future collisions and reconfigurations. But the chance of the first part of that chain, a major event on the San Andreas fault, happening in my lifetime is so small that I just don't see any point in worrying about it.

Think about it this way: there are no guarantees in life. None. There's no guarantee that the sun will rise in the morning tomorrow--there's only the probability that it will. Based on what we have observed in the past, there is an extremely high probability that in the morning, there it will be, the sun, shining forth as usual. We all go to sleep at night perfectly content that the odds are in our favor on this one. Well, I have the same attitude toward The Big One.

Then again--there was a small earthquake maybe two years ago, when I was at work, in Santa Monica. At the time I happened to be on my lunch break, sitting in the lobby of the building with a book in my hand. I felt the ground jump a little and then looked up--to realize that I was sitting in a glass-roofed extension of the lobby, and that these gigantic panes of glass were shivering above me.

And yeah, I'm not crazy--that made me a little nervous.

Monday, August 06, 2007

Free the Old Head!

Y'know, without context, that title looks more than a little odd...

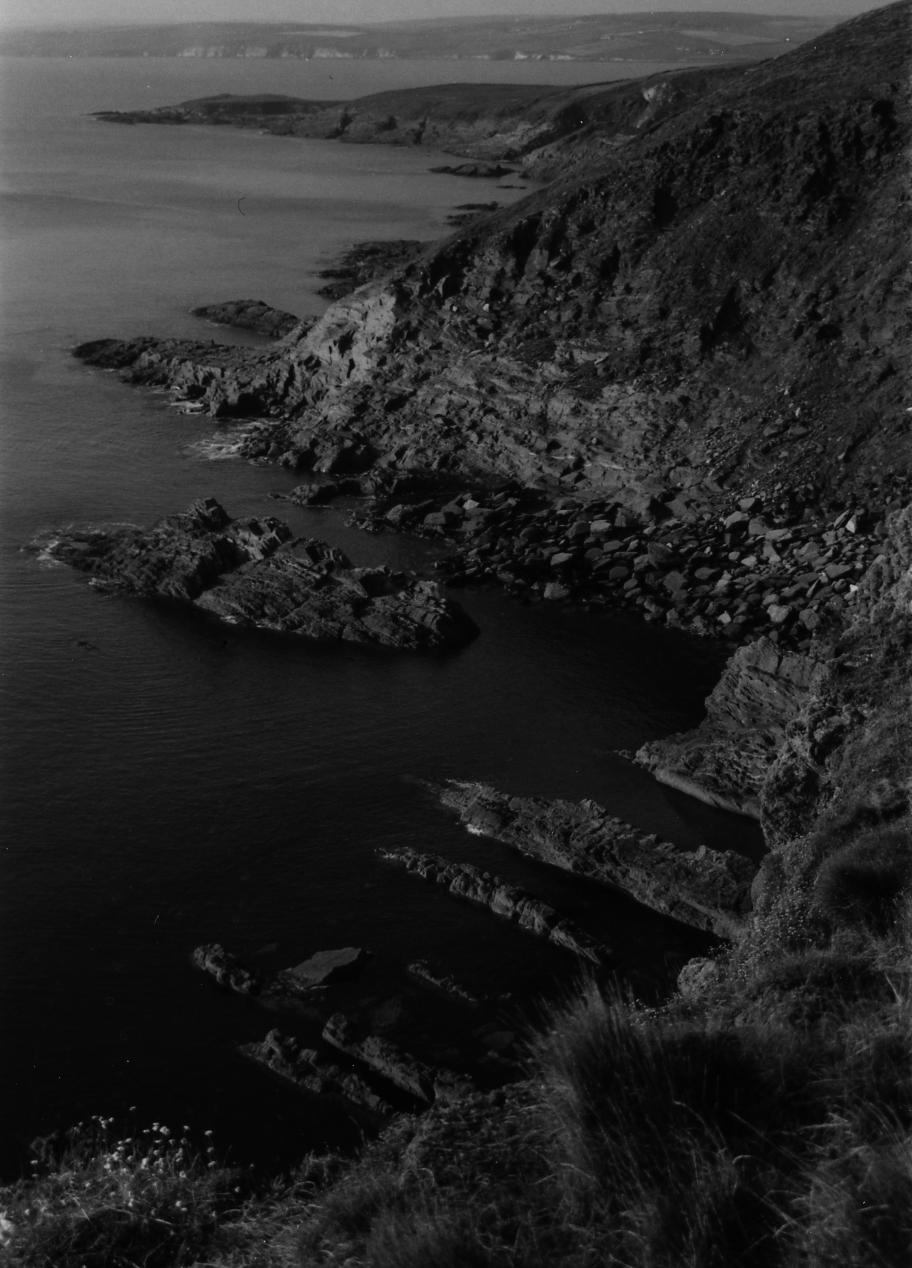

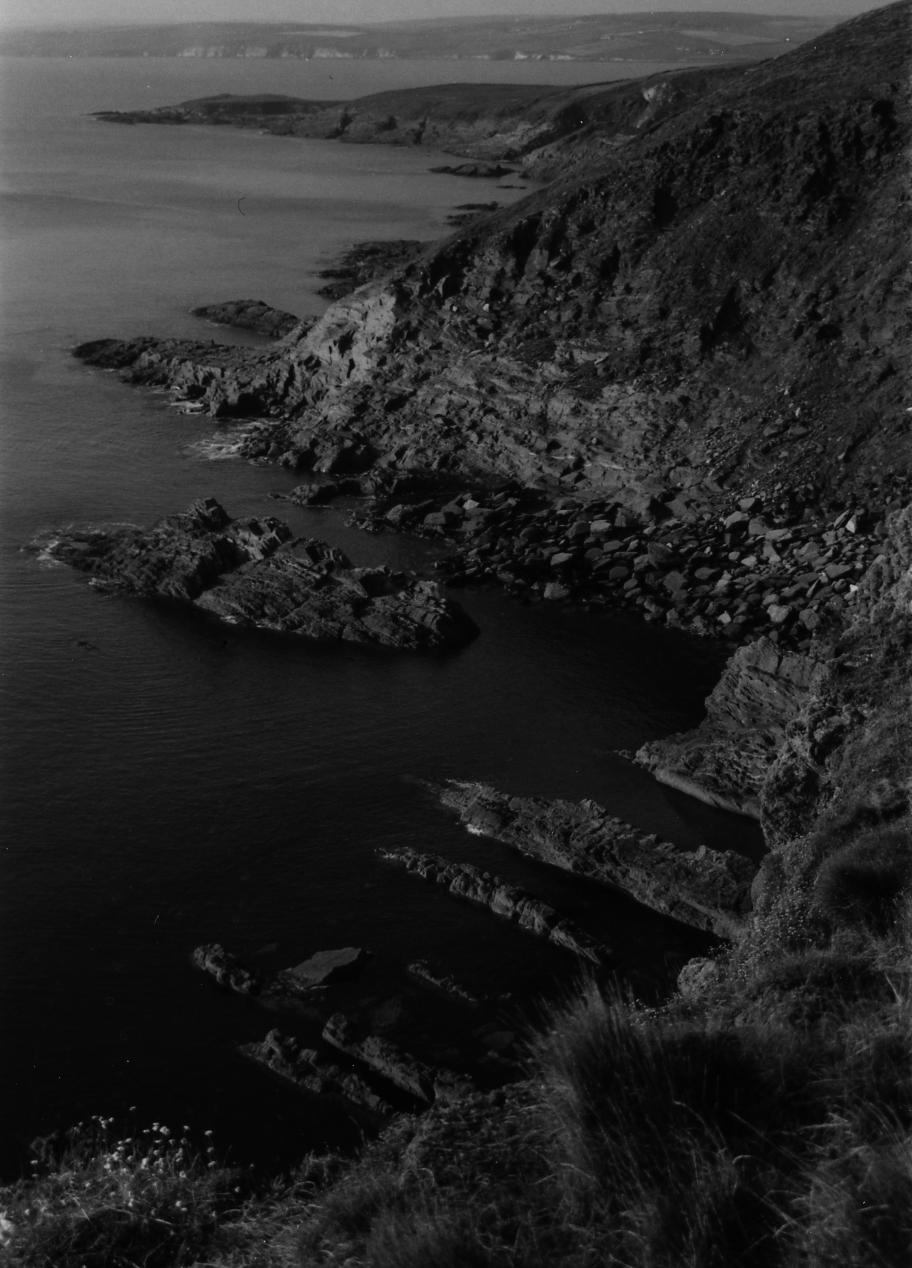

Yesterday I was channel-surfing and ended up watching most of a Discovery HD program on the sinking of the Lusitania, which was torpedoed just a few miles off the Irish coast in 1915--nearest a diamond-shaped strip of land that juts out into the Atlantic, known as the Old Head of Kinsale. As I've mentioned before, my grandparents lived in Kinsale for several years, my grandmother died there, and I've always loved the place--particularly the Old Head, which is one of the most beautiful places in the world. Here's proof:

(Mom took that picture, by the way; it's better than any of the ones I took.) The Old Head is one of those geological oddities, a strip of sandstone that will probably be an island someday when the narrow isthmus connecting it to the mainland erodes away, but that someday is very far off indeed. Back when my grandparents lived there, the Old Head simply was. You could go there whenever you liked and explore as much as you wished. And believe me, every time I went to Ireland I made sure to visit the Old Head. To wander for a couple hours, breathe the sea air, revel in the views, find that particular peace that comes with such a beautiful place. And honest, the goats never bothered me even once.

Ah yes, the goats. The stalwart defenders of the Old Head. If they decided they didn't like you, they were perfectly happy chasing you back to your car and then ramming it a few times to let you know that you were not welcome. They were just part of the charm, you see. As you can see from the photo, they were perfectly placid whenever I visited, which can certainly be chalked up to sheer chance, or maybe they just recognized that I too was someone who loved the place as much as they did. If only they had been able to defend the Old Head against the wretched forces of consumerism, then maybe...

Ah yes, the goats. The stalwart defenders of the Old Head. If they decided they didn't like you, they were perfectly happy chasing you back to your car and then ramming it a few times to let you know that you were not welcome. They were just part of the charm, you see. As you can see from the photo, they were perfectly placid whenever I visited, which can certainly be chalked up to sheer chance, or maybe they just recognized that I too was someone who loved the place as much as they did. If only they had been able to defend the Old Head against the wretched forces of consumerism, then maybe...

The last time I visited, I was given the bad news: some real estate developers had purchased the Old Head, and were planning to put a golf course on it. As an Old Head-loving member of the non-rich general public, I would never be able to go there again. And, indeed, I never have. The course opened ten years ago, and people have been shut out ever since. So when I saw this program on the Lusitania, I was again reminded of the Old Head. And of the enormous crime that has been perpetrated on the people of the world by the owners of that damn golf course.

I went to the course's website (no, I will not link to it, nor honor the place by mentioning its name). Green fees are 295 Euros, which is about $406 in U.S. currency. (For comparison, the legendary old course at St. Andrews, birthplace of golf and one of the homes of the British Open, only costs 125 Euros in the high season, or about $172.) That's not counting rental of a golf cart and a caddy. There's fine dining, for members only. And high fences with razor wire to keep people out.

On their site there is a video where they actually say that the course "helps nature fulfill its potential." As if nature wasn't already doing a spectacular job all on its own, which is why the wretched O'Connor brothers bought the place to begin with. They also advertise helicopter charters "for the discerning golfer," which "cuts out significant time lost on road travel, [and] alleviates time pressures...." Because, don't ya know, their visitors are so in-demand that they simply must be able to chopper in, play a few holes, then get the hell out without having to be bothered by, you know, the rabble on those twisty roads. Why, there's barely a straight road anywhere on the whole island, and you're constantly being stopped because there are sheep being herded across the road!

Of course, some of us see that as one of the great joys of Ireland: the pace is different, and being in a hurry is just plain wrong. Don't these people realize that if the point is to relax by playing a few holes, then stressing out by taking a helicopter in and out completely wrecks the whole thing? Those roads do not efficiently get you from Point A to Point B, no they don't; ain't it great?

But you've gotta love the web. I found this site, Free the Old Head of Kinsale, which is exactly what it sounds like: a site agitating for the Old Head to be opened again to the public. They're not trying to oust the golf course at all, they're not unrealistic about their goals: they simply want a trail, something, to be opened to the public so that the common folk can enjoy this most beautiful of places as they have for centuries. There is apparently a court case pending on this very issue of public right-of-way, and I dearly hope they prevail. In the meantime, there's a web petition you can sign, and I am extremely dismayed to find that my signature was only number 56. Maybe you might find yourself so moved as to visit the site and sign on as well. Here's another reason why you should:

Yesterday I was channel-surfing and ended up watching most of a Discovery HD program on the sinking of the Lusitania, which was torpedoed just a few miles off the Irish coast in 1915--nearest a diamond-shaped strip of land that juts out into the Atlantic, known as the Old Head of Kinsale. As I've mentioned before, my grandparents lived in Kinsale for several years, my grandmother died there, and I've always loved the place--particularly the Old Head, which is one of the most beautiful places in the world. Here's proof:

(Mom took that picture, by the way; it's better than any of the ones I took.) The Old Head is one of those geological oddities, a strip of sandstone that will probably be an island someday when the narrow isthmus connecting it to the mainland erodes away, but that someday is very far off indeed. Back when my grandparents lived there, the Old Head simply was. You could go there whenever you liked and explore as much as you wished. And believe me, every time I went to Ireland I made sure to visit the Old Head. To wander for a couple hours, breathe the sea air, revel in the views, find that particular peace that comes with such a beautiful place. And honest, the goats never bothered me even once.

Ah yes, the goats. The stalwart defenders of the Old Head. If they decided they didn't like you, they were perfectly happy chasing you back to your car and then ramming it a few times to let you know that you were not welcome. They were just part of the charm, you see. As you can see from the photo, they were perfectly placid whenever I visited, which can certainly be chalked up to sheer chance, or maybe they just recognized that I too was someone who loved the place as much as they did. If only they had been able to defend the Old Head against the wretched forces of consumerism, then maybe...

Ah yes, the goats. The stalwart defenders of the Old Head. If they decided they didn't like you, they were perfectly happy chasing you back to your car and then ramming it a few times to let you know that you were not welcome. They were just part of the charm, you see. As you can see from the photo, they were perfectly placid whenever I visited, which can certainly be chalked up to sheer chance, or maybe they just recognized that I too was someone who loved the place as much as they did. If only they had been able to defend the Old Head against the wretched forces of consumerism, then maybe...The last time I visited, I was given the bad news: some real estate developers had purchased the Old Head, and were planning to put a golf course on it. As an Old Head-loving member of the non-rich general public, I would never be able to go there again. And, indeed, I never have. The course opened ten years ago, and people have been shut out ever since. So when I saw this program on the Lusitania, I was again reminded of the Old Head. And of the enormous crime that has been perpetrated on the people of the world by the owners of that damn golf course.

I went to the course's website (no, I will not link to it, nor honor the place by mentioning its name). Green fees are 295 Euros, which is about $406 in U.S. currency. (For comparison, the legendary old course at St. Andrews, birthplace of golf and one of the homes of the British Open, only costs 125 Euros in the high season, or about $172.) That's not counting rental of a golf cart and a caddy. There's fine dining, for members only. And high fences with razor wire to keep people out.

On their site there is a video where they actually say that the course "helps nature fulfill its potential." As if nature wasn't already doing a spectacular job all on its own, which is why the wretched O'Connor brothers bought the place to begin with. They also advertise helicopter charters "for the discerning golfer," which "cuts out significant time lost on road travel, [and] alleviates time pressures...." Because, don't ya know, their visitors are so in-demand that they simply must be able to chopper in, play a few holes, then get the hell out without having to be bothered by, you know, the rabble on those twisty roads. Why, there's barely a straight road anywhere on the whole island, and you're constantly being stopped because there are sheep being herded across the road!

Of course, some of us see that as one of the great joys of Ireland: the pace is different, and being in a hurry is just plain wrong. Don't these people realize that if the point is to relax by playing a few holes, then stressing out by taking a helicopter in and out completely wrecks the whole thing? Those roads do not efficiently get you from Point A to Point B, no they don't; ain't it great?

But you've gotta love the web. I found this site, Free the Old Head of Kinsale, which is exactly what it sounds like: a site agitating for the Old Head to be opened again to the public. They're not trying to oust the golf course at all, they're not unrealistic about their goals: they simply want a trail, something, to be opened to the public so that the common folk can enjoy this most beautiful of places as they have for centuries. There is apparently a court case pending on this very issue of public right-of-way, and I dearly hope they prevail. In the meantime, there's a web petition you can sign, and I am extremely dismayed to find that my signature was only number 56. Maybe you might find yourself so moved as to visit the site and sign on as well. Here's another reason why you should:

Labels:

Entries with pictures,

Ireland,

Kinsale,

Old Head of Kinsale

Sunday, August 05, 2007

Coming Soon...

I looked around a couple months ago and realized that over the past few years I've started three companies. (Really, I looked around and there they were, strung in a line behind me, staring back and blinking.) There was the not-for-profit NOWtheatre back in Chicago, which alas does not exist anymore (this one seemed the most forlorn, and blinked only in memory), and then there are the quite-alive-and-still-blinking Zenmovie (an LLC) and Lightwheel Entertainment (a C corp.)

And I realized that every time I started one of those companies, I kept wishing that I could find, somewhere somehow, a list that would tell me the stuff I needed to know in one place: what documents are due to the various government agencies, federally and locally; how much money to pay; and on what dates said documents and payments are due. I scoured the internet blah blah blah, and never found such a document. So finally it occurred to me: I should make one.

So that's one of the things I've been doing. Finished the first draft about a month ago, whereupon my friend Buffie did an extraordinary annotation that led me through the second draft, which I finished last night. Now friend Marc will help me set up a website and, probably early next month, we'll launch the book on the web and see if others find it as useful as I believe it to be.

The book bears the beautiful and mellifluous title Incorporation for Artists, Writers, Musicians and Filmmakers. It ain't literature, it's information, which was an interesting challenge in itself, turning off all my let's call them Thereby-esque writing instincts, my automatic tendency toward the prolix, in order to just convey information. But that's one of the things Buffie is extraordinarily good at, so all praise to her, and I can't wait till we can get this little devil out into the world.

And I realized that every time I started one of those companies, I kept wishing that I could find, somewhere somehow, a list that would tell me the stuff I needed to know in one place: what documents are due to the various government agencies, federally and locally; how much money to pay; and on what dates said documents and payments are due. I scoured the internet blah blah blah, and never found such a document. So finally it occurred to me: I should make one.

So that's one of the things I've been doing. Finished the first draft about a month ago, whereupon my friend Buffie did an extraordinary annotation that led me through the second draft, which I finished last night. Now friend Marc will help me set up a website and, probably early next month, we'll launch the book on the web and see if others find it as useful as I believe it to be.

The book bears the beautiful and mellifluous title Incorporation for Artists, Writers, Musicians and Filmmakers. It ain't literature, it's information, which was an interesting challenge in itself, turning off all my let's call them Thereby-esque writing instincts, my automatic tendency toward the prolix, in order to just convey information. But that's one of the things Buffie is extraordinarily good at, so all praise to her, and I can't wait till we can get this little devil out into the world.

Sunday, July 22, 2007

Gotta Love Magic Hour

In case anyone was wondering "Why travel all the way to Vermont just to shoot a trailer?" I proffer the following:

I had never been to Vermont before, but quickly decided that it's a lot like Ireland: overwhelmingly green, with contours to die for, one of those places where you could pretty much close your eyes, point a camera at random, and get a good picture. The above was taken when I had no time to do anything but point and click, yet it looks like a postcard. Too damn easy. And if the point is to make something with visual oomph, well, this particular property in gorgeous Vermont does half our work for us.

I had never been to Vermont before, but quickly decided that it's a lot like Ireland: overwhelmingly green, with contours to die for, one of those places where you could pretty much close your eyes, point a camera at random, and get a good picture. The above was taken when I had no time to do anything but point and click, yet it looks like a postcard. Too damn easy. And if the point is to make something with visual oomph, well, this particular property in gorgeous Vermont does half our work for us.

(And besides--the people in town were unfailingly pleasant, and the food was beyond-belief-good. I was working like crazy and still gained four pounds in four days.)

After flying a red-eye, and driving up from Boston (loads of fun to be in Boston again, no matter how briefly), and checking into the hotel, we got off our first shot right at magic hour. A jib-arm shot that floated above a fence to reveal the teahouse, framed in Maxfield Parrish lighting (in fact, Parrish worked in New Hampshire, just next door, so no wonder). Here we've got actors Jennifer Ann Evans and David Goryl doing their thing, while director Marc Rosenbush and DP Chris Gosch do theirs. Me, I had just made the strange Blair Witch-thing, just visible beyond the camera, that was meant to disguise an electrical outlet that would have marred the beauty of the shot. We were supposed to have cloudy weather, with a too-high chance of rain; instead we walked into a painting and shot some film of it. Not bad.

After flying a red-eye, and driving up from Boston (loads of fun to be in Boston again, no matter how briefly), and checking into the hotel, we got off our first shot right at magic hour. A jib-arm shot that floated above a fence to reveal the teahouse, framed in Maxfield Parrish lighting (in fact, Parrish worked in New Hampshire, just next door, so no wonder). Here we've got actors Jennifer Ann Evans and David Goryl doing their thing, while director Marc Rosenbush and DP Chris Gosch do theirs. Me, I had just made the strange Blair Witch-thing, just visible beyond the camera, that was meant to disguise an electrical outlet that would have marred the beauty of the shot. We were supposed to have cloudy weather, with a too-high chance of rain; instead we walked into a painting and shot some film of it. Not bad.

The weather held all through the next day, during which we got the tricky shots: the ones that will require special effects, and compositing and green screens and so forth. There were the beautiful scenes at the teahouse, and at the mini-Stonehenge only a few yards away, and as were working on the last of the tricky effects shots, something blew the power main and we lost power, just as the sun was setting. The next day, it rained. Then rained some more. Then rained harder.

The weather held all through the next day, during which we got the tricky shots: the ones that will require special effects, and compositing and green screens and so forth. There were the beautiful scenes at the teahouse, and at the mini-Stonehenge only a few yards away, and as were working on the last of the tricky effects shots, something blew the power main and we lost power, just as the sun was setting. The next day, it rained. Then rained some more. Then rained harder.

Which is, of course, why everything is so green up there in green green Vermont. We got some interior shots, then started improvising, then kinda had to give up for a while. Went back to the hotel and everyone got a nap for a few hours, till sunset, when the rain finally stopped--and we grabbed a shot at the swimming pond behind the hotel instead of dashing back to the property to get what would have been a nearly identical shot. (Like I said: point a camera practically anywhere in Vermont and you're gonna get something good.)

In the end, we didn't get everything we wanted--but the question remains, did we get everything we needed? Yeah, I think maybe we did. The trailer will be less of a linear storyline and more a progression of interesting images, but that's fine, that's what most trailers are anyway. Now if only we had gotten footage of the time David got attacked by a giant badger...

I had never been to Vermont before, but quickly decided that it's a lot like Ireland: overwhelmingly green, with contours to die for, one of those places where you could pretty much close your eyes, point a camera at random, and get a good picture. The above was taken when I had no time to do anything but point and click, yet it looks like a postcard. Too damn easy. And if the point is to make something with visual oomph, well, this particular property in gorgeous Vermont does half our work for us.

I had never been to Vermont before, but quickly decided that it's a lot like Ireland: overwhelmingly green, with contours to die for, one of those places where you could pretty much close your eyes, point a camera at random, and get a good picture. The above was taken when I had no time to do anything but point and click, yet it looks like a postcard. Too damn easy. And if the point is to make something with visual oomph, well, this particular property in gorgeous Vermont does half our work for us.(And besides--the people in town were unfailingly pleasant, and the food was beyond-belief-good. I was working like crazy and still gained four pounds in four days.)

After flying a red-eye, and driving up from Boston (loads of fun to be in Boston again, no matter how briefly), and checking into the hotel, we got off our first shot right at magic hour. A jib-arm shot that floated above a fence to reveal the teahouse, framed in Maxfield Parrish lighting (in fact, Parrish worked in New Hampshire, just next door, so no wonder). Here we've got actors Jennifer Ann Evans and David Goryl doing their thing, while director Marc Rosenbush and DP Chris Gosch do theirs. Me, I had just made the strange Blair Witch-thing, just visible beyond the camera, that was meant to disguise an electrical outlet that would have marred the beauty of the shot. We were supposed to have cloudy weather, with a too-high chance of rain; instead we walked into a painting and shot some film of it. Not bad.

After flying a red-eye, and driving up from Boston (loads of fun to be in Boston again, no matter how briefly), and checking into the hotel, we got off our first shot right at magic hour. A jib-arm shot that floated above a fence to reveal the teahouse, framed in Maxfield Parrish lighting (in fact, Parrish worked in New Hampshire, just next door, so no wonder). Here we've got actors Jennifer Ann Evans and David Goryl doing their thing, while director Marc Rosenbush and DP Chris Gosch do theirs. Me, I had just made the strange Blair Witch-thing, just visible beyond the camera, that was meant to disguise an electrical outlet that would have marred the beauty of the shot. We were supposed to have cloudy weather, with a too-high chance of rain; instead we walked into a painting and shot some film of it. Not bad. The weather held all through the next day, during which we got the tricky shots: the ones that will require special effects, and compositing and green screens and so forth. There were the beautiful scenes at the teahouse, and at the mini-Stonehenge only a few yards away, and as were working on the last of the tricky effects shots, something blew the power main and we lost power, just as the sun was setting. The next day, it rained. Then rained some more. Then rained harder.

The weather held all through the next day, during which we got the tricky shots: the ones that will require special effects, and compositing and green screens and so forth. There were the beautiful scenes at the teahouse, and at the mini-Stonehenge only a few yards away, and as were working on the last of the tricky effects shots, something blew the power main and we lost power, just as the sun was setting. The next day, it rained. Then rained some more. Then rained harder.Which is, of course, why everything is so green up there in green green Vermont. We got some interior shots, then started improvising, then kinda had to give up for a while. Went back to the hotel and everyone got a nap for a few hours, till sunset, when the rain finally stopped--and we grabbed a shot at the swimming pond behind the hotel instead of dashing back to the property to get what would have been a nearly identical shot. (Like I said: point a camera practically anywhere in Vermont and you're gonna get something good.)

In the end, we didn't get everything we wanted--but the question remains, did we get everything we needed? Yeah, I think maybe we did. The trailer will be less of a linear storyline and more a progression of interesting images, but that's fine, that's what most trailers are anyway. Now if only we had gotten footage of the time David got attacked by a giant badger...

Labels:

Entries with pictures,

Trailer shooting,

Vermont

Sunday, July 15, 2007

Travelating

The idea is, make a trailer that looks like the next movie we want to make, and it becomes easier to make investors say "Hey, I want to see that movie!" so that we can, in fact, shoot the real thing. Film being, after all, a visual medium. Would you rather see a business plan or three minutes of footage?

That's why we're flying to Vermont tonight. A bunch of actors, some minimal crew, and an astonishing amount of checked baggage. We'll shoot for just a few days, be back by Friday, and then I get some real mileage out of Final Cut Pro.

And what have I been up to in the meantime? Well, getting ready for this, obviously, but also: finishing a treatment for a new screenplay, revising the City of Truth screenplay with Marc (incorporating a wealth of great feedback from several sources), defining the mission statement and purpose of Lightwheel Entertainment, and, happiest of all, rediscovering Thereby.

I posted an excerpt from Thereby Hangs a Tale a long while back, but hadn't actually read it in a time much longer than that. (The book itself has been basically finished for years--long enough that there is stuff in there about two towers being destroyed, collapsing with people in them, that most definitely predates Sept. 11th, and consequently becomes a bit of a problem--do you change the novel because it is, accidentally, too close to something real in a way that would be distracting? Unfortunately, the fall of my towers is so deeply integrated into the story itself that that would be pretty much impossible, so all I can do is have one of my characters, from the "real" world rather than the unnamed someplace where most of the novel happens, comment on the freakish coincidence.)

But since my friend Buffie was visiting, I happened to mention the novel to her one day, and realized I'd never actually shown it to her. So I pulled up the file, started reading, and had that happiest of discoveries: after a great deal of time, not only do I still like the book, I absolutely love it. So I zoomed through a touch-ups rewrite, happy to find that it was already in very good shape, and after getting some comments from people I will start working on finding exactly the right agent--someone who'll love it as much as I do.

Being in L.A. had kinda convinced me that Thereby was just too weird to ever sell, that's exactly why it sat for so long, unseen and unloved. But as soon as I started reading it again I realized, Hell no, it's not that weird at all, all it needs is the right agent and the right editor and the right marketing campaign, and I think people will go a little crazy over it.

But enough for now. Now, I have to pick up a fish-eye lens and then finish packing before a red-eye to Vermont. If there's an internet connection (we already know our cellphones will be just about useless) I'll try to check in from the road.

That's why we're flying to Vermont tonight. A bunch of actors, some minimal crew, and an astonishing amount of checked baggage. We'll shoot for just a few days, be back by Friday, and then I get some real mileage out of Final Cut Pro.

And what have I been up to in the meantime? Well, getting ready for this, obviously, but also: finishing a treatment for a new screenplay, revising the City of Truth screenplay with Marc (incorporating a wealth of great feedback from several sources), defining the mission statement and purpose of Lightwheel Entertainment, and, happiest of all, rediscovering Thereby.

I posted an excerpt from Thereby Hangs a Tale a long while back, but hadn't actually read it in a time much longer than that. (The book itself has been basically finished for years--long enough that there is stuff in there about two towers being destroyed, collapsing with people in them, that most definitely predates Sept. 11th, and consequently becomes a bit of a problem--do you change the novel because it is, accidentally, too close to something real in a way that would be distracting? Unfortunately, the fall of my towers is so deeply integrated into the story itself that that would be pretty much impossible, so all I can do is have one of my characters, from the "real" world rather than the unnamed someplace where most of the novel happens, comment on the freakish coincidence.)

But since my friend Buffie was visiting, I happened to mention the novel to her one day, and realized I'd never actually shown it to her. So I pulled up the file, started reading, and had that happiest of discoveries: after a great deal of time, not only do I still like the book, I absolutely love it. So I zoomed through a touch-ups rewrite, happy to find that it was already in very good shape, and after getting some comments from people I will start working on finding exactly the right agent--someone who'll love it as much as I do.

Being in L.A. had kinda convinced me that Thereby was just too weird to ever sell, that's exactly why it sat for so long, unseen and unloved. But as soon as I started reading it again I realized, Hell no, it's not that weird at all, all it needs is the right agent and the right editor and the right marketing campaign, and I think people will go a little crazy over it.

But enough for now. Now, I have to pick up a fish-eye lens and then finish packing before a red-eye to Vermont. If there's an internet connection (we already know our cellphones will be just about useless) I'll try to check in from the road.

Sunday, June 03, 2007

Better Bees?

Huh. Apparently time passes.

Can't say why exactly I'm so fascinated about the story of the bees, but I am. And perhaps even more interesting than the initial reports that caught my attention is the possibility that said reports are, shall we say, overstated. Neil Gaiman, often mentioned here, has recently become a beekeeper, and in his blog he quoted his "Bird Lady," Sharon Stiteler, who wrote to him, saying:

Also, the story about cell phone towers interfering with bees' navigation systems (which so captivated Bill Maher recently) may have been more than overstated, it may have been, according to an April 22 story in the International Herald Tribune, flat-out made up.

Imagine that: all that buzzing over nothing new. Aren't there enough really serious things wrong with the world without making up new ones? Next time: George Bush goes environmental. (That snickering you hear ain't just me...)

Can't say why exactly I'm so fascinated about the story of the bees, but I am. And perhaps even more interesting than the initial reports that caught my attention is the possibility that said reports are, shall we say, overstated. Neil Gaiman, often mentioned here, has recently become a beekeeper, and in his blog he quoted his "Bird Lady," Sharon Stiteler, who wrote to him, saying:

Our bees are Minnesota Hygienic Italian Bees developed by Marla

Spivak at the U of M[innesota]. She is one of the researchers studying Colony Collapse Disorder--she said that this has been a problem for the last 15 years and this year the media has grabbed on to the story. has studied the Varroa mite, which over the past 20 years has become a major threat to commercial honeybees. First discovered in the United States in 1987, the mite weakens the bee's immune system. It kills off most bee colonies within a year or two after invading. Beekeepers use pesticides to control the mites, but Spivak has studied ways to breed honeybees that are resistant to it. The bees have been bred to have a "hygienic" behaviors. They sense when brood is diseased and cleans them out. They also clean out any dead bees as well. This behavior cuts down on foul brood and other colony problems.

Also, the story about cell phone towers interfering with bees' navigation systems (which so captivated Bill Maher recently) may have been more than overstated, it may have been, according to an April 22 story in the International Herald Tribune, flat-out made up.

Imagine that: all that buzzing over nothing new. Aren't there enough really serious things wrong with the world without making up new ones? Next time: George Bush goes environmental. (That snickering you hear ain't just me...)

Sunday, April 29, 2007

Day and Date

I have to assume that Mark Cuban is a solid businessman who know what he's doing, but for the life of me I just can't figure out why he's promoting this whole day-and-date movie release scheme of his.

Cuban runs HDNet, one of the few cable channels that broadcasts exclusively in high definition. I've had a hi-def set for a few months now, attached to my hi-def Series 3 TiVo (one of the great inventions), and I love it. I'm a movie guy, so of course I love it, but what's not to love? Widescreen, great image detail, and it's attached to a good stereo with good speakers. I've even started pulling DVDs off my Netflix list if I saw they were going to be broadcast on an HD channel because they look better there. (And yes, I too am one of those waiting on the sidelines for the HD-DVD/Blu-Ray thing to work itself out before I commit to one machine or another.) So HDNet is one of my mainstays, and I particularly love it when they show some NASA footage--simply spectacular. (Though nothing so far has beat the recent Planet Earth specials on Discovery HD Theatre.)

But HDNet also has a movies-only hi-def channel, and the other night they ran a movie called Diggers. As it happens, I had heard about this movie a couple days before and thought it looked interesting: an offbeat indie about clam diggers, with a good cast including Paul Rudd, Sarah Paulson, Lauren Ambrose and Maura Tierney, all of whom I like. I noticed it was going to be playing at a theater only a few blocks away--a theater for which I have a free admission pass. So it was within easy walking distance and wouldn't cost me anything to go and see the movie. "Well maybe I'll do that," I said--but then I checked the TV listings and discovered that Diggers was also playing on HDNet, that same night.

I ask you, why would I want to go to the theater, then? It's more comfortable at home, my equipment is all first-rate, and I can watch when I want. About the only thing that might have made me go to a theater in such a circumstance would have been if I'd had a date, but that didn't happen to be the case. So I stayed home and recorded it on the TiVo and was completely happy. But, as I say, baffled.

Because bear in mind: I'm a movie guy. And I certainly have a keen appreciation for the power of a shared theatrical experience by an audience of strangers experiencing something together (by the way, for the record, Zen Noir works best on a movie screen; I'm just saying, I've seen it happen over and over, that really is the ideal way to see it). I was already motivated to see this particular film, the theater was in easy walking distance, I like to walk, and I had a pass to see the movie for free. It was, in short, about as easy as going to a movie theater can possibly be--but I didn't go, and the only reason I didn't is because that same movie was showing that same night on my TV.

That's what day-and-date means, and it mystifies me. It refers to a newfangled way to release movies in which the movie is broadcast and shown in theaters on the same night, then gets released on DVD the next Tuesday: all formats show up at once, and people can have their choice of watching it in any way they prefer. Nice for we the viewers, but where is the business model? How is Cuban making any money off this?

Sure, Wagner gets my money as a subscriber to the channel, but he gets that anyway; and now he's lost my theater-going money (well, except for that free admission pass, but that's not really germane). The one thing you most don't want to happen is what happens: one format cannibalizes the possibility for success of another format. I paid nothing to watch it on TV, and did not pay anything to watch it in a theater. They tried this with Steven Soderbergh's Bubble several months ago, and lo and behold, that movie did lousy at the box office. (According to Box Office Mojo, it made $145,000, with a production budget of $1.6 million.)

I don't think I'm being a stuffy old traditionalist about this, and I admit the possibility that Cuban is smarter than I am, but I just don't see how he's making any money here. But in the meantime, what the heck: I've got this lovely movie sitting on my TiVo, I think I'll go watch it now.

Cuban runs HDNet, one of the few cable channels that broadcasts exclusively in high definition. I've had a hi-def set for a few months now, attached to my hi-def Series 3 TiVo (one of the great inventions), and I love it. I'm a movie guy, so of course I love it, but what's not to love? Widescreen, great image detail, and it's attached to a good stereo with good speakers. I've even started pulling DVDs off my Netflix list if I saw they were going to be broadcast on an HD channel because they look better there. (And yes, I too am one of those waiting on the sidelines for the HD-DVD/Blu-Ray thing to work itself out before I commit to one machine or another.) So HDNet is one of my mainstays, and I particularly love it when they show some NASA footage--simply spectacular. (Though nothing so far has beat the recent Planet Earth specials on Discovery HD Theatre.)

But HDNet also has a movies-only hi-def channel, and the other night they ran a movie called Diggers. As it happens, I had heard about this movie a couple days before and thought it looked interesting: an offbeat indie about clam diggers, with a good cast including Paul Rudd, Sarah Paulson, Lauren Ambrose and Maura Tierney, all of whom I like. I noticed it was going to be playing at a theater only a few blocks away--a theater for which I have a free admission pass. So it was within easy walking distance and wouldn't cost me anything to go and see the movie. "Well maybe I'll do that," I said--but then I checked the TV listings and discovered that Diggers was also playing on HDNet, that same night.

I ask you, why would I want to go to the theater, then? It's more comfortable at home, my equipment is all first-rate, and I can watch when I want. About the only thing that might have made me go to a theater in such a circumstance would have been if I'd had a date, but that didn't happen to be the case. So I stayed home and recorded it on the TiVo and was completely happy. But, as I say, baffled.

Because bear in mind: I'm a movie guy. And I certainly have a keen appreciation for the power of a shared theatrical experience by an audience of strangers experiencing something together (by the way, for the record, Zen Noir works best on a movie screen; I'm just saying, I've seen it happen over and over, that really is the ideal way to see it). I was already motivated to see this particular film, the theater was in easy walking distance, I like to walk, and I had a pass to see the movie for free. It was, in short, about as easy as going to a movie theater can possibly be--but I didn't go, and the only reason I didn't is because that same movie was showing that same night on my TV.

That's what day-and-date means, and it mystifies me. It refers to a newfangled way to release movies in which the movie is broadcast and shown in theaters on the same night, then gets released on DVD the next Tuesday: all formats show up at once, and people can have their choice of watching it in any way they prefer. Nice for we the viewers, but where is the business model? How is Cuban making any money off this?

Sure, Wagner gets my money as a subscriber to the channel, but he gets that anyway; and now he's lost my theater-going money (well, except for that free admission pass, but that's not really germane). The one thing you most don't want to happen is what happens: one format cannibalizes the possibility for success of another format. I paid nothing to watch it on TV, and did not pay anything to watch it in a theater. They tried this with Steven Soderbergh's Bubble several months ago, and lo and behold, that movie did lousy at the box office. (According to Box Office Mojo, it made $145,000, with a production budget of $1.6 million.)

I don't think I'm being a stuffy old traditionalist about this, and I admit the possibility that Cuban is smarter than I am, but I just don't see how he's making any money here. But in the meantime, what the heck: I've got this lovely movie sitting on my TiVo, I think I'll go watch it now.

Labels:

Day and date,

HDNet,

Hi-def rules,

How movies are marketed,

Indie films

Thursday, April 26, 2007

Where Could They Bee?

Since I was just writing recently about bees, I would be remiss if I did not mention that the bees seem to be going on vacation. Or, to be a little more scientific about it, they're disappearing. By the billions.

As the various articles point out, food crops that rely on honeybees for pollination are worth about $15 billion and include a lot of the fruits and nuts that we all love the most: apples, cherries, almonds, and so forth. There is no adequate mechanical substitute for the pollinating prowess of the honeybee, so if this unknown process should continue, it is reasonable to expect that these staples of our diet will not disappear but will become very expensive from simple scarcity. (Imagine a ten dollar slice of pie.) (Okay, in Los Angeles that's not so far from the truth, but imagine it in Dubuque.)

Bee colonies started to collapse last October: huge numbers of worker bees would simply never return to the hive, up to 50% of the colony in many cases. As CNN reports, most of these bees just plain vanished, and their little bee bodies were never found. Since their failure to return was possibly a failure in their navigation systems, speculation ran rampant on all sorts of causes, including cellphone towers (leading Bill Maher last week to ask, "will we choose to literally blather ourselves to death?"). This New York Times article goes into more detail on the science involved, including this disturbing photo of cross-sections of diseased (left) and healthy (right) bee thoraxes:

A chemical trigger for all this seems most likely, particularly since some hives treated with gamma radiation have begun to recover, suggesting that the gamma is killing some yet-unknown pathogen. But research has barely begun on the problem, and all the while, the bees keep disappearing; and despite some lucky breaks, like the fact that Baylor College of Medicine recently happened to finish sequencing bee DNA (thus speeding up immeasurably a search for genetic triggers), we have no idea how long it will take to find answers to this problem.

Diseased bees are being found to be contaminated with fungi common in humans whose immune systems have been depressed by AIDS or cancer. Thus we learn yet again, we're all connected. The question then becomes, if the bees go, what happens to us?

As the various articles point out, food crops that rely on honeybees for pollination are worth about $15 billion and include a lot of the fruits and nuts that we all love the most: apples, cherries, almonds, and so forth. There is no adequate mechanical substitute for the pollinating prowess of the honeybee, so if this unknown process should continue, it is reasonable to expect that these staples of our diet will not disappear but will become very expensive from simple scarcity. (Imagine a ten dollar slice of pie.) (Okay, in Los Angeles that's not so far from the truth, but imagine it in Dubuque.)

Bee colonies started to collapse last October: huge numbers of worker bees would simply never return to the hive, up to 50% of the colony in many cases. As CNN reports, most of these bees just plain vanished, and their little bee bodies were never found. Since their failure to return was possibly a failure in their navigation systems, speculation ran rampant on all sorts of causes, including cellphone towers (leading Bill Maher last week to ask, "will we choose to literally blather ourselves to death?"). This New York Times article goes into more detail on the science involved, including this disturbing photo of cross-sections of diseased (left) and healthy (right) bee thoraxes:

A chemical trigger for all this seems most likely, particularly since some hives treated with gamma radiation have begun to recover, suggesting that the gamma is killing some yet-unknown pathogen. But research has barely begun on the problem, and all the while, the bees keep disappearing; and despite some lucky breaks, like the fact that Baylor College of Medicine recently happened to finish sequencing bee DNA (thus speeding up immeasurably a search for genetic triggers), we have no idea how long it will take to find answers to this problem.

Diseased bees are being found to be contaminated with fungi common in humans whose immune systems have been depressed by AIDS or cancer. Thus we learn yet again, we're all connected. The question then becomes, if the bees go, what happens to us?

Friday, April 20, 2007

I Have No Mouth and I Must Kvetch

Meanwhile, on a lighter note...

Went last night to a screening of an unfinished documentary called "Dreams With Sharp Teeth," about the inimitable Harlan Ellison. (Does anyone ever just write his name, or is there always some sort of adverb in front of it?) (Just found the trailer, here.) I've been a fan of Harlan's for way over twenty years now, since my mom read Shatterday then handed it over to me. It was one of those thunderbolts from the blue you get sometimes: words on a page with such vigor and imagination that you immediately respond by going out and buying every other book by this guy you can possibly find.

then handed it over to me. It was one of those thunderbolts from the blue you get sometimes: words on a page with such vigor and imagination that you immediately respond by going out and buying every other book by this guy you can possibly find.

It's hard to describe Harlan, because there are so many colors to his gigantic personality. Well into his 70s now, he is on the one hand a short, cranky Jew from Painesville, Ohio with the emotional life of an 11 year old; he is also an extremely serious artist in a complex, lifelong pas de deux with his muse; he is a raconteur of the first order, a fearsome debater who will absolutely get right up in your face, one of the most honored writers of his time, a moralist who is utterly unafraid to be offensive, a fanboy collector with a house full of stuff called, no kidding, "Ellison Wonderland," and a sweet guy who loves his friends like crazy. Which is exactly why a documentary about him is such a great idea.

The screening was at the Writers Guild Theatre on the wrong part of Doheny Drive. (Woe to you if you plug in the address on your Mapquest search with "Los Angeles" rather than "Beverly Hills." O woe!) The director, who I believe is Erik Nelson (there isn't yet an imdb listing for the film), has been following Harlan around with a camera since 1981 ("I always just thought he was a fanboy!" cracked Ellison), so clearly this was a labor of love--because believe me, if there wasn't love, Harlan would've driven anyone else away within about ten minutes. Because I was so late (damn you, Doheny!) I missed the first fifteen minutes or so, arriving just in time for the section where Harlan joined the army. By this point the audience--full of Harlan's friends--was already laughing hysterically. They barely needed the film's pithy sidebars (re: Ellison and the army, "It was not a relationship destined for success"), but it was a night for laughter, the loving kind: a guy who's lived a full life, surrounded by people he loved (and name-dropping like crazy), getting what amounted to a valedictory celebration of his life.

It may be a fault of the film that it is in fact too valedictory, that none of Harlan's many enemies weren't interviewed--but then, Harlan is so firm in his convictions that you get the impression he regrets nothing and will defiantly stand behind everything he has ever done in his entire life. And when you start to talk about his enemies, the man just cackles with glee, already rolling up his sleeves and preparing for a new battle. He is that rarest of things in this passive-aggressive world of surface politeness but hidden meanness of spirit: a man who plants his feet and stands behind everything he says, who sugarcoats nothing, and who is so much smarter than pretty much anyone that if said anyone gets caught on the wrong side of an argument with Harlan, well, good luck. But if you are a friend, he is just as passionate: he will come up, embrace you in a bear hug and kiss you on the cheek while saying the most wildly flattering things (there's a section of the film about Harlan the ladies' man that, again, got a good rolling laugh out of the crowd).

Josh Olson, the Oscar-nominated screenwriter of A History of Violence, moderated the discussion with Harlan after the film and could barely hold it together because Harlan was (literally) all over the place, with Erik Nelson's cameraman and boom guy following desperately, trying to keep up. Werner Herzog was in the audience, so was the great musician Richard Thompson, along with Battlestar Galactica creator Ronald D. Moore and of course Harlan's marvelous wife Susan. Harlan was profane and raucous, and if there's any justice some of this material will get folded into the documentary before it gets released because jeez what a night.

But really, when you talk about Harlan you must talk about the work. Shatterday is a good place to begin: it contains some very good short stories like the famous "Jeffty is Five," the title story, and the delicious "All the Birds Come Home to Roost" in which a man encounters all his ex-girlfriends in reverse chronological order, leading inevitably to the first and worst. There are probably better collections (Strange Wine and Deathbird Stories

and Deathbird Stories immediately come to mind) (and man, it's a crime how many of his books are out of print), but I might particularly recommend Stalking the Nightmare

immediately come to mind) (and man, it's a crime how many of his books are out of print), but I might particularly recommend Stalking the Nightmare , the second book of his I read, the one that really cemented my love for the man and his work. Because this time, in addition to some very good short stories, there are also three tales directly from his life, including the hilarious one in which he worked at Disney for exactly one morning then got himself fired.

, the second book of his I read, the one that really cemented my love for the man and his work. Because this time, in addition to some very good short stories, there are also three tales directly from his life, including the hilarious one in which he worked at Disney for exactly one morning then got himself fired.

In some ways, I like Ellison the essay writer even more than Ellison the short story writer. An Edge in My Voice stands as the absolute best of his essay collections, although the two Glass Teat books (about television) are better known. But really, you should probably start with The Essential Ellison

stands as the absolute best of his essay collections, although the two Glass Teat books (about television) are better known. But really, you should probably start with The Essential Ellison , a fifty-year overview of his work containing much of the best of everything. Then go watch the documentary when it comes out, and start agitating various publishers to get these books back in the marketplace, damn it!

, a fifty-year overview of his work containing much of the best of everything. Then go watch the documentary when it comes out, and start agitating various publishers to get these books back in the marketplace, damn it!

Went last night to a screening of an unfinished documentary called "Dreams With Sharp Teeth," about the inimitable Harlan Ellison. (Does anyone ever just write his name, or is there always some sort of adverb in front of it?) (Just found the trailer, here.) I've been a fan of Harlan's for way over twenty years now, since my mom read Shatterday